I'll segue into today's topic with an update on the status of the game I'm working on. It's kind of what prompted the question in the title - that and some recent conversation on the social platforms.

I was also working on a separate ruleset beforehand, for a heist game. There were various iterations, and I was largely happy with it, but it was more of a pet project than the Fantasy Heartbreaker. Then I started running a new campaign, and... well, I don't remember my thinking exactly, but the fantasy game has been absorbed into that heist game.

I mean, a dungeon crawl is just a heist anyway, we all know this. This is simply a ruleset that leans into certain aspects of the dungeon crawl over others, with a particular implied setting, all of which add up to make a more "heist"-themed game that still plays in the OSR style. I'm very proud of it so far, and I expect you'll be hearing more about it soon enough.

***

The heist game as it existed before the fantasy stuff got absorbed into it had no specific combat rules. Combat was a governed by a roll, like other things, and that was fine. It worked for the genre and tone of that system.

I had notions of bringing over mechanics from the fantasy ruleset to keep things in line with what I thought of as OSR - things like initiative, attack rolls, AC.

The core mechanic of the heist game is very different from d20+mod, and I had a lot of fun trying to adapt those classic concepts in new ways, thinking up new mechanics that delivered the same effects. But as I refined the game, playtested, drafted and redrafted, all those mechanics fell by the wayside.

In the latest iteration, the one I'm using to run stuff, combat is just a roll again. There are as many combat rules as there are rules for stealth, lockpicking or scaling a clock tower in the dead of night with a grappling hook. That is to say: describe what you want to do, and then the GM tells you to make a roll.

My designer brain, reared on 5e and now enamoured of the many DIY takes on traditional combat systems, keeps throwing up ideas on adding tactics, damage types, weapon categories. But nothing works as well for this system as the single roll.

***

My next thought, then, was "is this still OSR?". I know from Troika! that the old-school mechanics OSR games draw inspiration from don't have to be from D&D, and I know from Maze Rats that you can change the core mechanic until it's not recognisably D&D at all and still be considered OSR.

But no combat rules? Surely this was blasphemy? Was I turning my face from the DIY community entirely, and embracing some new, dark wilderness of game design, alone?

I mean... no. I don't think so.

***

One of the most persistent myths about the old-school style is that it's a numbers-first, tactical combat based, hack-and-slash style of gameplay. It's not. The game is lethal, and if you wish to avoid the many varieties of grisly demise on offer, you need to think creatively, avoiding and subverting combat scenarios rather than engaging in them.

But you knew that, you're smart. We all on the same page? Good.

So, then, quoth the as-yet-unaware, why do OSR systems have so many combat rules? As opposed to, say, rules for feeling things, or exploration? If the game is about things other than combat, why isn't that reflected in its ruleset?

Again, we know the answer: because the way OSR play engages with the rules is fundamentally different from most other schools of RPG design. Your character sheet is a list of the few limitations imposed on you, not a list of your awesome powers and skill trees. In something like Pathfinder, say, the character sheet represents all the cool stuff you can do. In an OSR system, the cool stuff you can do is everything else. OSR play is what's not written - what's written is there to ground the situation and make things difficult.

***

So, then, the if the purpose of the combat rules in an OSR system is to enforce lethality, the question we started off with remains. Does an OSR game need dedicated combat rules?

No. I don't think so.

What it needs is lethality rules - rules that ensure that when things go wrong, there are drastic and often fatal consequences. Rules that encourage the OSR playstyle - player ingenuity and calculated risk-taking - by providing a box the player is forced to think outside of.

The reason, then, that these lethality rules have been presented as combat rules since the days of yore is, obviously, partly because the hobby evolved out of wargaming. But if that was the only reason, they would have been replaced over the decades as RPGs moved further and further from their wargaming roots.

The main reasons, I think, are a combination of genre conventions and player agency. We expect the knight to have a sword, and know how to use it, while the wizard shoots fireballs from her trusty staff. Those are the special skills the characters offer, and since we can't roleplay physical danger at the table like we can social situations or intellectual puzzles, we need to have at least some idea of whether or not they will work in a given instance.

This ties heavily in to player agency. When your back's against the wall and combat's the only option, you want to know exactly what it is you can do - even if it is likely a fatal endeavour.

Combat rules do three things, then: enforce lethality, support the expected tone and setting of the system, and allow players options to fall back on when "standard play" (what I call just, like, talking), fails them. These are all Good Things. Combat rules are good.

***

So why was I having such a hard time grafting them on to my own system? Why did every attempt feel so inelegant? It is an OSR game, I still believe that. The playstyle is exactly the same. I eventually realised I'd just achieved that playstyle in a different way.

My game has its own rules to enforce lethality that aren't tied to damage. I'll likely detail them another time, or they'll be available to read once some form of playtest doc or rulebook comes out. But basically, rolls are inherently dangerous. Every one is a gamble with your character's fate, in one way or another, and with each failure you risk slipping closer and closer to death. The structure of lethality is very much enforced, even without standard HP mechanics or damage rolls.

As for supporting the expected tone and setting? Well, those are different in this game. It's not a gonzo Conan-esque dungeon crawl, it's kept too much of the heist flavour for that. I still run dungeon crawls in it, but the setup and tone are different enough that players don't expect their characters to necessarily be able to wield a sword, or use magic. In fact, character creation makes it very apparent how unlikely it is that either of those skills will be available. It's in a different genre, ish.

And finally, options to fall back on. The numbers on the sheet, the stuff outside of talking, planning, or using your surroundings or inventory in interesting ways. Those three things are the vast majority of any session, but what happens when those options fail? Combat mechanics sort that out by giving everyone some kind of mechanical sway on the deadly situation, however slight. Characters in my game still have mechanical abilities, but not everyone has an attack bonus. They'll be good in other ways - hiding from a monster, sneaking past it, running away.

Don't get me wrong - they can attack. Limiting player agency is maybe the biggest no-no for me in game design. They're just probably not going to be good at it. Making them good enough at a bunch of other stuff, and making that stuff more relevant, is an acceptable substitute, I've found.

***

So, to answer the question.

tl;dr: No.

I figured out that:

1. Lethality mechanics don't need to be distinctly combat-focused as long as failure can still lead to death and disaster.

2. Players won't miss dedicated combat rules if the setting and style make it clear that combat is unlikely to be relevant.

3. As long as the players have something to roll for when the shit hits the fan, they're happy, even if it's not a classic attack roll vs AC.

***

The only thing remaining, then, is compatibility with other OSR/DIY stuff, and I don't think the game's lacking anything by not basing itself on the standard model. The main point of conversion between systems is monster stat blocks, and since there aren't any combat rules, the game doesn't need 'em. You could absolutely run something like Tomb of the Serpent Kings in this system, no problem.

Well, that's me all rambled out. Exciting things to come, stay tuned.

Tuesday 22 May 2018

Wednesday 16 May 2018

On Mermaids, Hashtag Mermay

So a bunch of artists on Twitter (and, I presume, your social media platform of choice) are doing a thing. It's been a thing for a few years now I think? Anyway, in the month of May, they draw mermaids.

I found all the art in this post from artists I follow and by searching the hashtag. Check em out and hire em for stuff.

Mermaids are also great for fantasy games. Here's the how and why.

Soundtrack for this post.

There are two types of mermaid; not in historical mythology, just in current fantasy art and media, as observed by me.

The first type is the classic, storybook - even, Disney - mermaid. Top half pretty naked lady or, less commonly, man, and bottom half big ol' fish. (Side note: as far as we can tell, mermen predate mermaids. Huh.)

The second type incorporates the fishiness throughout. Blue scale-like skin, fin-ears, kelp hair, even barracuda teeth or, god forbid, gills.

Before we get into things, it would be remiss of me to not mention the fantastic Kiel Chenier's upcoming Weird on the Waves pirate setting kit, in which mermaids are a playable race. He's teased the variants: top half fish, or left half fish, or one where the fish bits are all inside. Can't wait for that.

(I guess I'll tag him here so people can find his stuff? I still have zero idea how or why Google Plus is a thing, but I think this'll do it? +KielChenier )

Let's talk about the first one first.

These mermaids are perfect for your fantasy game. If you describe a skeleton floating blobbily in a square mass, that one player who's read the monster manual or been playing for 30 years is gonna go "Oh! It's a gelatinous cube!", to dumbfounded expressions from the rest of your group.

If you describe a naked woman coming out of the water, her lower half hidden beneath the waves, everyone's gonna be thinking the same thing. And when you describe her long, elegant tail flipping lazily in and out of the water, everyone's gonna be on the same page. Everyone knows what mermaids are. They share a prized place with dragons and unicorns as being seeped into the cultural consciousness of not just modern western civilisation, but pretty much the whole dang planet.

But while dragons are for killing, or avoiding, or maybe talking to but then at some point killing, and unicorns are for... I dunno, riding? Unicorns are boring. Anyway, these "type one" mermaids send out a pretty clear signal, unlike almost every other fantasy monster, that you can just talk to them. For us running our OSR games, this is a godsend. Yeah, it's a monster on a random encounter, but this monster is... nice. She's smiling, she's happy to help. Anyone's first port of call is going to be at least attempting communication.

And from there, mermaids can open up your world in other ways. Half of her's up here, sure, but half of here is very much from... down there. What you get is instant worldbuilding, the implication that at the very least there's a coral castle or a sunken fortress or a clan of merrily singing fishladies on a rock somewhere nearby.

An interaction with a monster that everyone instantly understands, that encourages communication and that, even in passing, fleshes out your world? As far as OSR play goes, that's a fucking win.

And sure, maybe they drown sailors for fun, that bit's up to you.

The "type two" mermaids then. The monsters.

Under the sea is weird. We know this. There are things down there that are more otherworldly than any sci fi movie's alien imaginings. These mermaids generally do a crappy-to-passable job of translating that otherness, but there's certainly untapped potential in the depths.

The problem here is, that if you want to go weird, there are better options than mermaids. The recognisable factor that makes the type-ones work so well puts you at a disadvantage here. It's like Cthulu: once a cosmic nightmare, vast and potent beyond our primate understanding, now a plushie you can get on a million Etsy stores, and the mascot for every other nerd-culture card game Kickstarter.

What these mermaids do best is in translating as animals, as beasts. I haven't played The Witcher III, but I've watched my girlfriend play it enough to know it's pretty great, and very Dungeons and Dragons. I once saw her rowing a little boat around the game's Viking-world analogue, when sirens attacked. I think that's what they're called in the game; in any case, sirens and mermaids have been conflated into mostly the same thing since forever.

These were no seashell bra-clad maidens, nor were they deep sea aliens. These were proper monsters. They were big, like sharks, and they tore into the boat as much as they did lovably gruff protagonist Geralt (I call him Jerry). We weren't knights on a quest, hearing the perilous siren's call, and we hadn't stumbled into anyone's non-euclidean eldritch domain. They were predators, and we were in their territory.

They weren't unknowable creatures from depths hitherto untravelled, or beautiful yet deadly temptresses. There are talking monsters in the Witcher, and fairytale stuff, but these just kinda... screamed. It was awesome. Sure they were vaguely human shaped, but the uncanny valley didn't even factor into it.

That's how you make type two mermaids work. Wait until the players are splashing around Amity Beach, and then let em loose. I'm not generally a fan of the whole "this monster is just an animal in its ecosystem, here's how it functions biologically" vibe, but as with my previous foray into trolls, sometimes it just works.

So there you go, some thoughts on mermaids. I think they're often overlooked, but worth your time.

They also feature in the setting of my current home game, and I'm trying to collate my notes into something playable so that I can share it. I'll likely slap on some art and a hexmap and call it a module. Stay tuned for news on when and how you can get it, probably in a couple of months.

There's a whole lot more than mermaids going on in my little setting, and you could certainly run a campaign without bumping into one. All I'll say is that I've managed to work both the "type one" and "type two" mermaids in there, and it's working very nicely.

It's pretty simple actually. Freshwater and saltwater.

I found all the art in this post from artists I follow and by searching the hashtag. Check em out and hire em for stuff.

Mermaids are also great for fantasy games. Here's the how and why.

Soundtrack for this post.

|

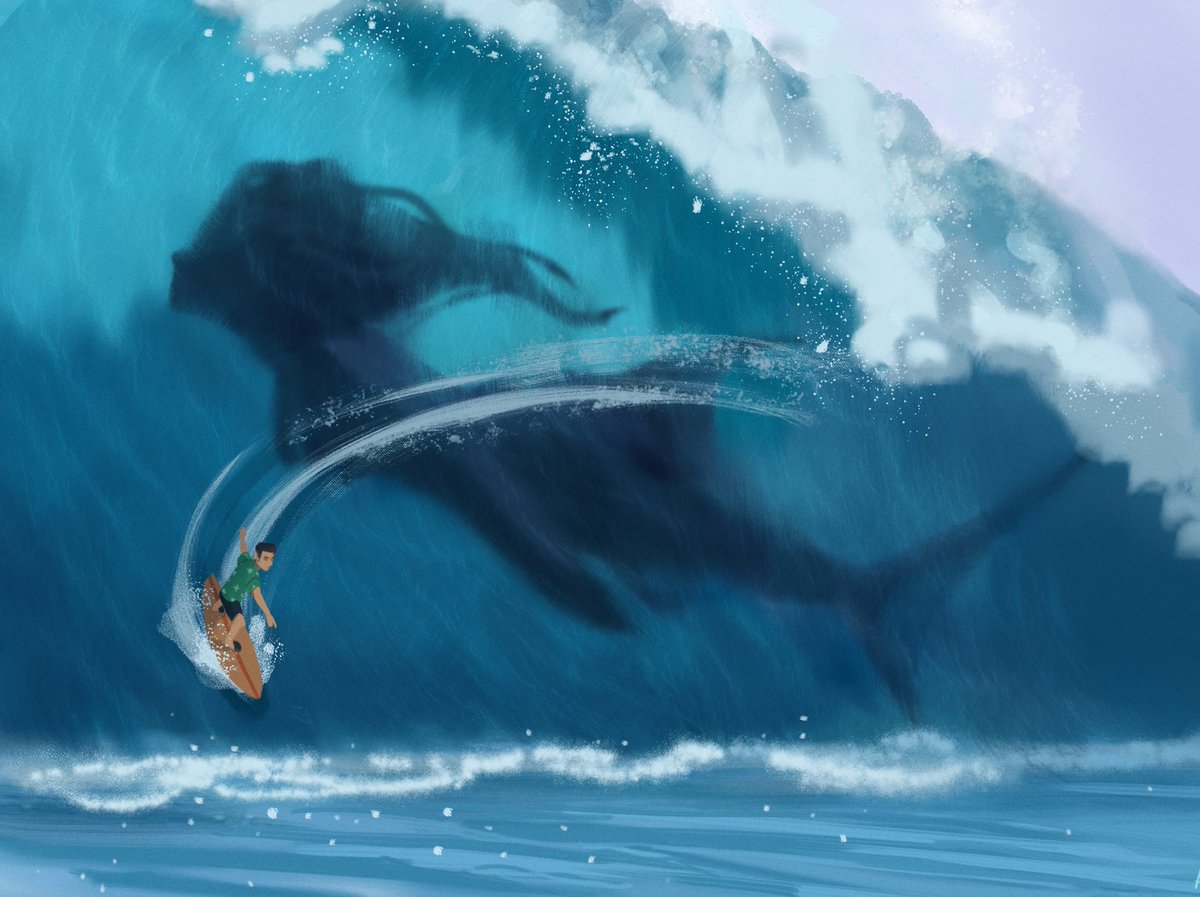

| art by @pkyrachu |

The first type is the classic, storybook - even, Disney - mermaid. Top half pretty naked lady or, less commonly, man, and bottom half big ol' fish. (Side note: as far as we can tell, mermen predate mermaids. Huh.)

The second type incorporates the fishiness throughout. Blue scale-like skin, fin-ears, kelp hair, even barracuda teeth or, god forbid, gills.

Before we get into things, it would be remiss of me to not mention the fantastic Kiel Chenier's upcoming Weird on the Waves pirate setting kit, in which mermaids are a playable race. He's teased the variants: top half fish, or left half fish, or one where the fish bits are all inside. Can't wait for that.

(I guess I'll tag him here so people can find his stuff? I still have zero idea how or why Google Plus is a thing, but I think this'll do it? +KielChenier )

Let's talk about the first one first.

|

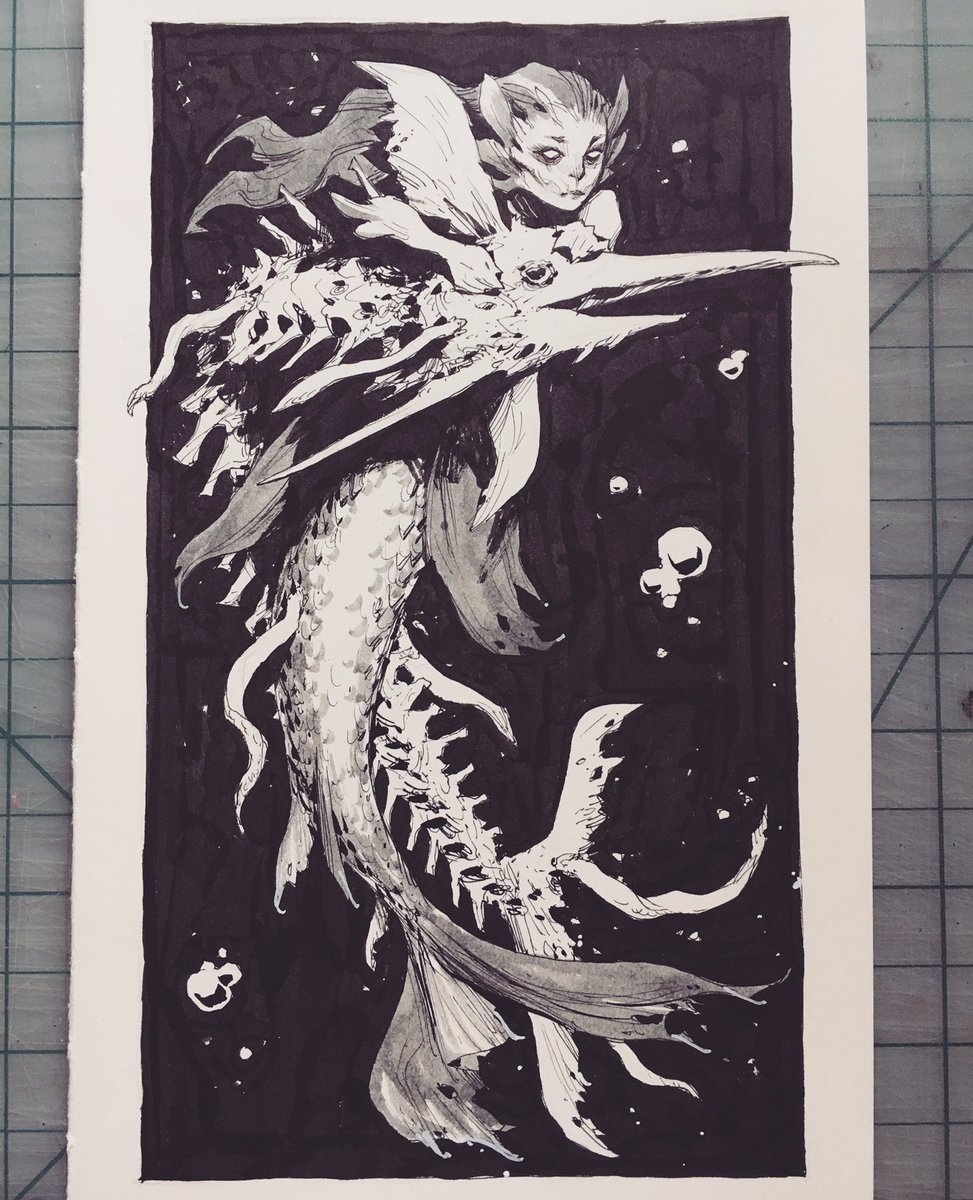

| art by @anamericanghost |

These mermaids are perfect for your fantasy game. If you describe a skeleton floating blobbily in a square mass, that one player who's read the monster manual or been playing for 30 years is gonna go "Oh! It's a gelatinous cube!", to dumbfounded expressions from the rest of your group.

If you describe a naked woman coming out of the water, her lower half hidden beneath the waves, everyone's gonna be thinking the same thing. And when you describe her long, elegant tail flipping lazily in and out of the water, everyone's gonna be on the same page. Everyone knows what mermaids are. They share a prized place with dragons and unicorns as being seeped into the cultural consciousness of not just modern western civilisation, but pretty much the whole dang planet.

But while dragons are for killing, or avoiding, or maybe talking to but then at some point killing, and unicorns are for... I dunno, riding? Unicorns are boring. Anyway, these "type one" mermaids send out a pretty clear signal, unlike almost every other fantasy monster, that you can just talk to them. For us running our OSR games, this is a godsend. Yeah, it's a monster on a random encounter, but this monster is... nice. She's smiling, she's happy to help. Anyone's first port of call is going to be at least attempting communication.

And from there, mermaids can open up your world in other ways. Half of her's up here, sure, but half of here is very much from... down there. What you get is instant worldbuilding, the implication that at the very least there's a coral castle or a sunken fortress or a clan of merrily singing fishladies on a rock somewhere nearby.

An interaction with a monster that everyone instantly understands, that encourages communication and that, even in passing, fleshes out your world? As far as OSR play goes, that's a fucking win.

And sure, maybe they drown sailors for fun, that bit's up to you.

|

| art by @andrewkmar |

Under the sea is weird. We know this. There are things down there that are more otherworldly than any sci fi movie's alien imaginings. These mermaids generally do a crappy-to-passable job of translating that otherness, but there's certainly untapped potential in the depths.

The problem here is, that if you want to go weird, there are better options than mermaids. The recognisable factor that makes the type-ones work so well puts you at a disadvantage here. It's like Cthulu: once a cosmic nightmare, vast and potent beyond our primate understanding, now a plushie you can get on a million Etsy stores, and the mascot for every other nerd-culture card game Kickstarter.

What these mermaids do best is in translating as animals, as beasts. I haven't played The Witcher III, but I've watched my girlfriend play it enough to know it's pretty great, and very Dungeons and Dragons. I once saw her rowing a little boat around the game's Viking-world analogue, when sirens attacked. I think that's what they're called in the game; in any case, sirens and mermaids have been conflated into mostly the same thing since forever.

These were no seashell bra-clad maidens, nor were they deep sea aliens. These were proper monsters. They were big, like sharks, and they tore into the boat as much as they did lovably gruff protagonist Geralt (I call him Jerry). We weren't knights on a quest, hearing the perilous siren's call, and we hadn't stumbled into anyone's non-euclidean eldritch domain. They were predators, and we were in their territory.

They weren't unknowable creatures from depths hitherto untravelled, or beautiful yet deadly temptresses. There are talking monsters in the Witcher, and fairytale stuff, but these just kinda... screamed. It was awesome. Sure they were vaguely human shaped, but the uncanny valley didn't even factor into it.

That's how you make type two mermaids work. Wait until the players are splashing around Amity Beach, and then let em loose. I'm not generally a fan of the whole "this monster is just an animal in its ecosystem, here's how it functions biologically" vibe, but as with my previous foray into trolls, sometimes it just works.

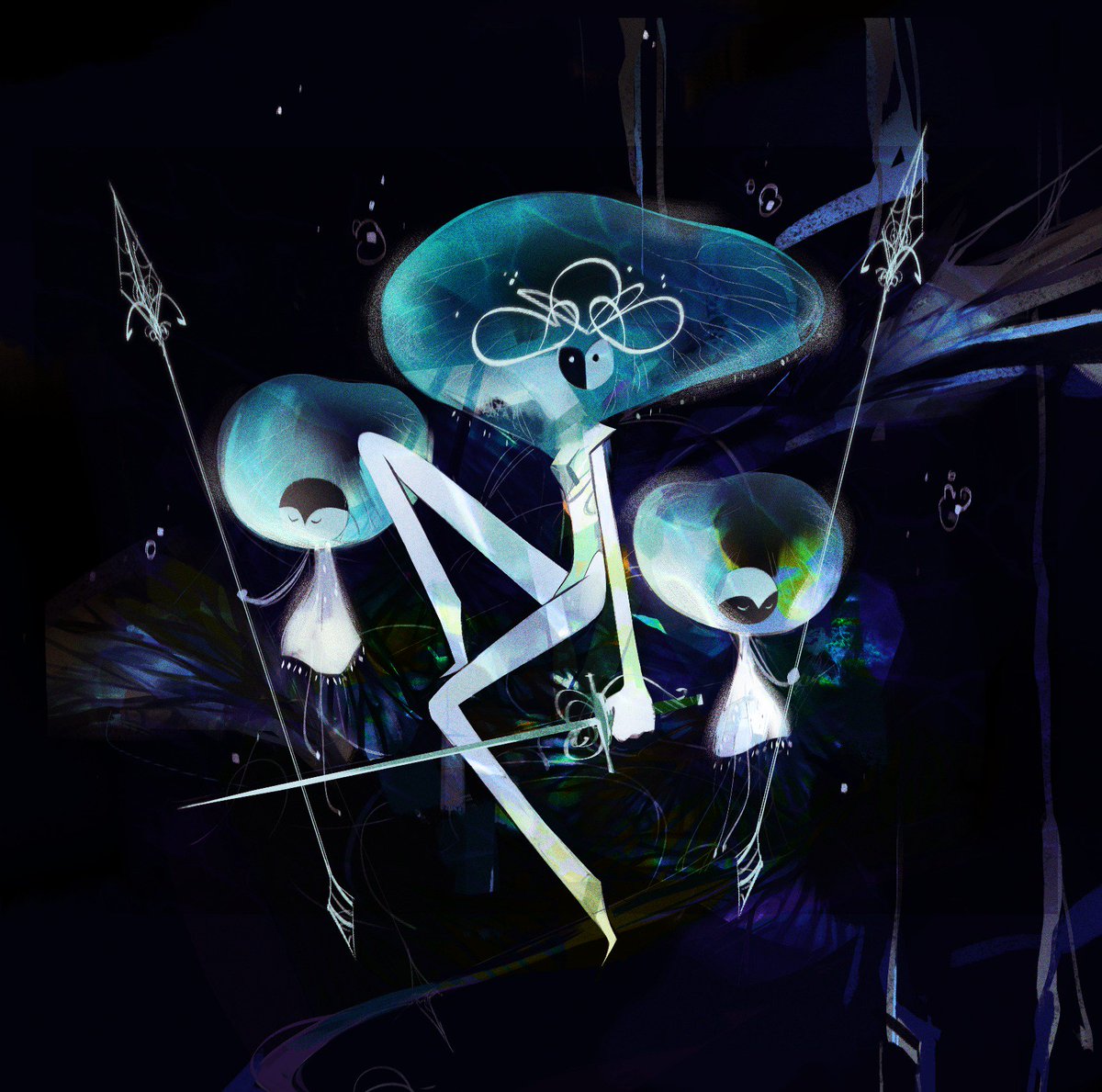

|

| art by @hairytentacles |

They also feature in the setting of my current home game, and I'm trying to collate my notes into something playable so that I can share it. I'll likely slap on some art and a hexmap and call it a module. Stay tuned for news on when and how you can get it, probably in a couple of months.

There's a whole lot more than mermaids going on in my little setting, and you could certainly run a campaign without bumping into one. All I'll say is that I've managed to work both the "type one" and "type two" mermaids in there, and it's working very nicely.

It's pretty simple actually. Freshwater and saltwater.

Monday 7 May 2018

Hell on the Moon (Part Two)

Part One can be found here.

***

The Dungeon

The dungeon is what people call the strange underground

construction in the next crater over from the diner. It takes about an hour to

reach on foot, and half as long by hoverbike.

What nobody remembers is that the dungeon was once a starship, called the Méliès, which crash landed into the surface years ago. The ship was crewed by moon elf priests who sook to travel the cosmos fighting demons.

What nobody remembers is that the dungeon was once a starship, called the Méliès, which crash landed into the surface years ago. The ship was crewed by moon elf priests who sook to travel the cosmos fighting demons.

However on one mission, demons took over the ship. The

priests tried to make it back home to get help, but by the time they reached

the moon it was clear the demons were too powerful and would pose a danger to

the empire. They sealed the demons in the top half of the ship and sacrificed

themselves by crash landing it into an empty crater.

The Méliès, upside down, is almost completely buried in moon

rock. At the end waits the demon lord, who has turned the cockpit into his

throne room. Lower down the ship, or rather, further up the dungeon, the plants

that the priests grew in their living quarters have overtaken the space and

turned it into an indoor jungle, where more demons roam.

The engine room, at the top of the dungeon, is sealed off

from the lower sections, and native moon creatures have made it their home.

What was once the ship’s exhaust is now an entrance, poking out just above the

lunar surface.

The Nest

The lower half of the ship, now the upper half of the

dungeon, has been taken over by moon bugs.

The engine room, maintenance

corridors and storage are all overgrown with nests made from the goo they

excrete. It hardens, covering surfaces and forming new, organic platforms and

pathways among the plain metal interior.

At the bottom of this area are two different hatches leading

down to the next section, both locked from this side. They open to anyone with

an Engineer’s Pass.

Nest Material

The calcified mess that coats everything will burn easily,

giving off a low, steady purplish light and noxious fumes for up to an hour.

The fire doesn’t spread though.

The Bugs

The eggs are fist-sized and gross. The larvae are helpless

and squeal if disturbed. The bugs are parasites, and will latch onto things to

kill and then take control of them.

The old crew of the Méliès stagger around, skeletons dressed

in priest robes and armour, piloted by the bugs on their skulls. They still

carry blessed swords and 1d4 moon coins each, as well as Engineer’s Passes

which can lock and unlock the doors between this section and the next.

The Others

In one corner of one corridor is a slight spatial shimmer,

detectable to anyone with magic. Astral somethings leak through on occasion

(1d20):

1: Like a huge

fat wheel made of flesh, with eyes in a pattern on either side. Could pull a

cart if you stuck a rope through the mucus-lined hole in its centre.

2: Tall and gangling, there is no

way to understand its language. Politely dismissive, it leaves.

3: Little yellow goblin-shaped crystal people. They eat anything intricate or complicated.

4: A teeny tiny spaceship full of little chaps, pootling through the air real slow like.

5: Noises like someone’s scraping two galaxies together.

6: Moon maidens. Not this moon. Like jellyfish or scraps of cloth in the wind or dancing women.

7: A big, severed hand, the wound cauterised.

8: Like a head with arms. If it bites you with its circular mouth it dies, and your skin turns purple.

9: Two-dimensional and pastel coloured, they disappear instantly when looked at sideways.

10: Like phytoplankton under a microscope, but hand-sized. They make music when touched.

11: A moon rock. Not this moon, though.

12: Part of a buckle for the equestrian gear certain celestials use to ride storms.

13: Green slime.

14: Bricks. Part of a tiefling’s stone spaceship.

15: An odd tool, presumably for repairing some otherworldly machine.

16: An engraved hammer. Summons lightning, or it would if there were clouds on the moon.

17: A big, severed hand, the wound adorned with a golden and jewelled cap. Mobile.

18: A coating of glittery dust. Causes skin to become pearlescent, and invisible in starlight.

19: A hat that projects the wearer’s surface-level thoughts as sound. Hard to remove once worn.

20: Tall, tentacle-faced, eats brains. You know the ones.

3: Little yellow goblin-shaped crystal people. They eat anything intricate or complicated.

4: A teeny tiny spaceship full of little chaps, pootling through the air real slow like.

5: Noises like someone’s scraping two galaxies together.

6: Moon maidens. Not this moon. Like jellyfish or scraps of cloth in the wind or dancing women.

7: A big, severed hand, the wound cauterised.

8: Like a head with arms. If it bites you with its circular mouth it dies, and your skin turns purple.

9: Two-dimensional and pastel coloured, they disappear instantly when looked at sideways.

10: Like phytoplankton under a microscope, but hand-sized. They make music when touched.

11: A moon rock. Not this moon, though.

12: Part of a buckle for the equestrian gear certain celestials use to ride storms.

13: Green slime.

14: Bricks. Part of a tiefling’s stone spaceship.

15: An odd tool, presumably for repairing some otherworldly machine.

16: An engraved hammer. Summons lightning, or it would if there were clouds on the moon.

17: A big, severed hand, the wound adorned with a golden and jewelled cap. Mobile.

18: A coating of glittery dust. Causes skin to become pearlescent, and invisible in starlight.

19: A hat that projects the wearer’s surface-level thoughts as sound. Hard to remove once worn.

20: Tall, tentacle-faced, eats brains. You know the ones.

The Hideout

One side room is sealed off, with no signs of the bugs having

ever entered. A wasted skeleton in priest robes has the Demon Key around its

neck and 3 moon coins. On the wall is scratched: LORD PROTECT ME.

The Jungle

What was once the living quarters of the Méliès is now a

demon-ridden jungle. Locked hatches separate it from the engine room above, and

a single central hatch leads to the cockpit below, where the demon lord

resides. The whole space is under the effect of an antimagic field, put in

place by the priests to keep the demons at bay.

Wandering Encounters (1d8):

1: Greater Demon.

2-3: 1d4 Lesser Demons.

4: An imp.

5: 1d4 imps.

6: 1d4 Lesser Demons with imps.

7: A wandering Shuffler.

8: Two Greater Demons, too concerned with their own business to notice the players.

2-3: 1d4 Lesser Demons.

4: An imp.

5: 1d4 imps.

6: 1d4 Lesser Demons with imps.

7: A wandering Shuffler.

8: Two Greater Demons, too concerned with their own business to notice the players.

Remnants

A few things remain of the ship’s previous occupants. When

searching a room, or the stash looted by a demon, you find (1d10):

1: A holy symbol.

2: Old priest robes, matching those

worn by the skeletons in the nest.

3: A smooth gemstone, the colour of another world’s sky.

4: A diary detailing proper care and caution of one of the plants found on the ship (roll 1d4 below for a plant).

5: 1d4 moon coins.

6: A manual for the ship’s communications array, in the cockpit.

7: A love note.

8: A spell book containing a cleric spell.

9: A dagger made of meteorite.

10: Medicine for a condition only moon elves suffer. Turns human skin red, permanently.

3: A smooth gemstone, the colour of another world’s sky.

4: A diary detailing proper care and caution of one of the plants found on the ship (roll 1d4 below for a plant).

5: 1d4 moon coins.

6: A manual for the ship’s communications array, in the cockpit.

7: A love note.

8: A spell book containing a cleric spell.

9: A dagger made of meteorite.

10: Medicine for a condition only moon elves suffer. Turns human skin red, permanently.

Plants

The crew of the Méliès grew plants in their living quarters

to brighten up the place. Since their death, the emergency lighting and water

systems have allowed the house plants to thrive, turning the space into an

indoor jungle. Vines cover the walls, mangroves take root in the bathrooms, and

palm trees grow upside down, planted in what used to be the floor.

Some plants may prove more interesting. (1d4):

1: Star Anemones.

These fleshy flower-like creatures grow out of walls. They grab at passers-by

and grip them tight, slowly dissolving pieces of them.

2: Laddervine. When tugged, it retracts, pulling anyone holding it upwards.

3: Shuffler. Mobile carnivorous plants that use a mess of roots to pull themselves around and grab food to put into their sticky, mouth-like flowers.

4: Meatleaf. Wide and rubbery leaves, filled with a jelly that vaguely resembles fish steak. Can be cooked, dried and cured into jerky. The smell of the raw jelly is appetising to simple, carnivorous beasts.

2: Laddervine. When tugged, it retracts, pulling anyone holding it upwards.

3: Shuffler. Mobile carnivorous plants that use a mess of roots to pull themselves around and grab food to put into their sticky, mouth-like flowers.

4: Meatleaf. Wide and rubbery leaves, filled with a jelly that vaguely resembles fish steak. Can be cooked, dried and cured into jerky. The smell of the raw jelly is appetising to simple, carnivorous beasts.

Imps

Little fat red-skinned idiots with wings, they zip around

and can disappear in a puff of acrid smoke. Would never deign to question the

rule of their superiors, but despise serving them. Everything they do, they do

out of fear of punishment.

Lesser Demons

By default they look like people with horns – you know,

demons. A group of 1d4 has 1d4 of the following extra features between them

(1d20):

1: Useless fly wings

and big insect eyes. Advantage on Perception.

2: A big crab claw on one oversized arm. 1d10 damage.

3: Craters down its back that expel lazy trails of smoke. 1d4 damage if you breathe near it.

4: Fur that drips something.

5: Big tusked jaws. 1d6 damage.

6: Another arm.

7: Another leg.

8: A scorpion tail. Bonus attack, 1d6 damage.

9: Hands for feet.

10: One big sideways mouth all the way up its torso. 2d4 damage.

11: A snake for genitals. Bonus attack, 1d4 damage.

12: Two heads.

13: Two more arms.

14: Eyes on its butt cheeks.

15: One arm is a tentacle. Double melee range, advantage to grapple.

16: Tiny head. Its bite is unlikely to hit, but turns a limb to stone.

17: Goat legs.

18: Backwards feet.

19: Bat wings.

20: Roll 1d6 twice and put the second one where the first should be (1: head, 2: arm, 3: leg, 4: mouth, 5: eye, 6: ass).

2: A big crab claw on one oversized arm. 1d10 damage.

3: Craters down its back that expel lazy trails of smoke. 1d4 damage if you breathe near it.

4: Fur that drips something.

5: Big tusked jaws. 1d6 damage.

6: Another arm.

7: Another leg.

8: A scorpion tail. Bonus attack, 1d6 damage.

9: Hands for feet.

10: One big sideways mouth all the way up its torso. 2d4 damage.

11: A snake for genitals. Bonus attack, 1d4 damage.

12: Two heads.

13: Two more arms.

14: Eyes on its butt cheeks.

15: One arm is a tentacle. Double melee range, advantage to grapple.

16: Tiny head. Its bite is unlikely to hit, but turns a limb to stone.

17: Goat legs.

18: Backwards feet.

19: Bat wings.

20: Roll 1d6 twice and put the second one where the first should be (1: head, 2: arm, 3: leg, 4: mouth, 5: eye, 6: ass).

Greater Demons

The henchpersons of the demon lord, they ensure his commands

are fulfilled. Each has a lock of some kind affixed to them, a gift from their

lord that makes them more useful to him in some way – whether it grants them

power or restricts it. Each lock has a keyhole, all of which can be unlocked by

the Demon Key.

1: Not quite 10ft

tall, strikingly handsome nude male with jet black hair, crimson skin and

brunette goat’s legs. He wears a blindfold, a keyhole in the centre.

Six imps accompany him, chained. They act as eyes, telling

him truths sprinkled with compliments. If less than three are able to speak to

him he is considered blind and will rage helplessly. If the blindfold is taken

off he will scramble to find a mirror. If he sees a mortal with his own eyes he

begins to age backwards rapidly until he is ash.

2: A little

taller than a person, feminine with pink-red skin, wearing only a complex

looking chastity belt. The belt has a bestial, toothy mouth with a keyhole in

its tongue.

She stuffs imps into the belt’s mouth and it eats their

heads. She’d love to get the belt off, truth be told, but the only way she can

think of involves someone losing an arm.

3: Huge towering

slime-thing, a wretched waste of a being.

Chained up in a dank corner somewhere, he knows all about

what’s going on, and most importantly where the Demon Key is that will free

him. He keeps this secret from his fellow demons, but will beg strangers to get

it for him, promising great reward. Unchained, he will begin to eat and will

not stop eating.

4: Tall, humanoid

but the proportions are wrong. Its head is encased in a helmet – glowing eyes,

keyhole in the back of the skull.

It is inactive, slumped. It will obey the one who inserts

the key in its head, moving slowly but with incredible strength.

5: Like a

centaur, but the horse part is a demon (too many legs!), and the human part is

a construction, a metal and wood automaton in the shape of an elegant woman –

four arms, impressive horns and a blank face. There is a keyhole in the navel.

If unlocked, the halves detach. The top half is full of

teeth, and can be locked into place on any suitable mount. The resulting

creature has the consciousness of the lower half, which dies.

6: Immobile and

trapped in a locked chest.

A mess of tentacles and thorns, she quite likes the chest,

and wants to fill it with money and treasure.

7: Tall and

androgynous, in flowing red robes. The Demon Key opens a lock on the side of

their head and the pretty, pallid face comes off.

They will always prefer a different face to the one they

have.

8: Little old

woman with red skin, white hair and tiny horns.

She made the locks that are on all the others, and will make

a new Demon Key for any of them if they ask.

Demon Lord

Corpulent and imposing, the demon lord lounges atop his

throne, eating imps and ordering his subordinates around. He’s pretty ok with

things just as they are. Wields a powerful demonic flail, and holds a horn that

summons hellfire when blown.

In his throne room are several imps, a few lesser demons

trying to be entertaining, and the rest of the Méliès crew, long-rotted and impaled

on spikes.

The room was once the ship’s cockpit, and a large window now

looks out onto solid rock. The ship’s controls are dented and battered.

Assuming someone could clear out the dungeon enough to give her space to work,

Nadia could repair the ship, reverse it out of the rock. She’ll let you keep it

if she likes you.

Notes

-

The challenge in this dungeon does not come from

progression being difficult. The only path that’s blocked are the locked doors

leading to the jungle and all the skeletons in area 1 have keys. If players

want to keep moving, they can, but they’ll miss information and go into the

final room severely unprepared. That’s where challenge comes in; finding out

what’s going on, who they can side with, and formulating a plan in the midst of

all the deadly weirdos.

-

The Reputation quests are a side thing and not

meant to be difficult. Make the first one or two incredibly simple – the

players simply stumble upon the jukebox part as they do their normal dungeon

delving. Then, leave it up to the players. If they want to pursue more errands

for Gramps and Nadia, let them, but don’t force it.

-

Obviously, the players could leave the moon before

they restore the Méliès, on one of the other passing ships. Have a lil bit of whatever

comes after this adventure prepped in case.

Sunday 6 May 2018

Hell on the Moon (Part One)

An adventure. Written to be a bridge from earth-bound shenanigans to Spelljammer-esque planar travel, but use as you wish, obvs.

To begin, the players are stranded on the moon.

***

For ages, the people

of the world observed, studied, even worshipped the moon. Little did they know

it was a world of its own.

The lunar surface is a

desolate wasteland of constant night. Bare white rock, covered in huge craters,

stretches endlessly under a permanently black and starry sky.

1000 years ago – Elves inhabit the moon, their empire is at its height

1000 years ago – Elves inhabit the moon, their empire is at its height

700 years ago – Decline begins, more and more leave for new

realms of the cosmos

150 years ago – The moon elf temple-ship Méliès crash lands

on the lunar surface

100 years ago – Gramps opens his diner

20 years ago – The last moon elves leave, only Gramps and

his diner remain

17 years ago – Nadia comes to live with her grandfather,

opens a garage outside the diner

Now – The players arrive on the moon

The Diner

In the middle of a lonely crater, the sole remaining vestige

of the moon elf empire is a dusty old drive-through, run by an elderly moon elf

known as Gramps, and his granddaughter Nadia. Although the rest of the empire

left long ago, passing ships still stop by on occasion to grab a bite to eat. Nadia

also runs a garage service, fixing up ships and recharging their engines with

the light of the large crystal that juts from the ground out back.

Gramps

A curmudgeonly old moon elf, he’s been running the diner for

a century. When the rest of the empire packed up and left, he stuck around. He

runs the diner with a mix of pride and obligation, brewing his famous moonshine

and serving up space food for the few space travellers who still stop by. He’ll

lend you a room and offer a meagre meal each day, as long as he gets to make a big show of how begrudging he is

about the whole thing.

Nadia

Gramps’ granddaughter lives with him at the diner. While she

does dream of someday leaving the lonely rock like the rest of the moon elves,

she loves her grandfather and feels a certain duty to help him. She loves

working with machines, whether it’s running the garage at the diner and working

on passing ships, or tinkering with her own pride and joy, a hoverbike. She’ll

offer to give the players lifts to the dungeon on it.

Reputation

Players might choose to help Gramps and Nadia restore the

diner by completing certain quests for them. Reputation is a stat that

represents the effects of this ongoing restoration. For each quest completed,

increase the diner’s Reputation by 1. The higher the diner’s Reputation, the

better known it will become and the more customers will stop by.

Gramps’ Quests

-

The jukebox needs fixing. There is a simple

replacement part somewhere in the dungeon’s Nest section.

-

If Gramps is feeling sentimental, he might reminisce

about a classic dish he used to have on the menu, but can’t make anymore

because he lacks the ingredients. Unbeknownst to him, the fruit he needs for

the sauce grows in the dungeon’s Jungle section.

-

If Gramps had a transmitter, he could broadcast

an advertisement for the diner over the airwaves to passing ships. There is a

working transmitter in the Throne Room at the end of the dungeon.

Nadia’s Quests

-

Nadia asks the players to bring back any power

couplings they come across, as she can use them to soup up her hoverbike. There

are power couplings in the Nest section of the dungeon. After she gets one,

Nadia’s hoverbike can make the journey to the crater in half the time.

-

There is a certain hard-to-find tool that might

be hanging around the maintenance corridors in the Nest section of the dungeon.

Nadia doesn’t know it’s there, but it would help her work in the garage no end.

(The players might not know what it is when they see it, but tell them it looks

like the kind of thing Nadia uses.)

Players may think of their own ways of helping the moon

elves with their business. Reward any creative and well-executed plans with a

Reputation point or two.

Visitors

Every night, the diner opens. Roll a die on the table below

to determine what customers show up. The die rolled depends on the diner’s

current Reputation. If the diner’s reputation is 5+, it is assumed there are a

few generic customers around in addition to the table result.

Reputation

|

Die

|

0

|

1d4

|

1

|

1d6

|

2

|

1d8

|

3

|

1d10

|

4

|

1d12

|

5+

|

2d12

|

1d4+

1: It’s a quiet night tonight.

2: Two-tailed moon jackals barking at the crystal out back. Shoo, ya varmints! Go on, get!

3: A lone alien, stopping in for some grub while he refuels his ship. He doesn’t speak.

4: Delivery! Food for the kitchen, a replacement part for some gadget, something X ordered.

1d6+

5: Loudmouth no-good punk kids on a joyride.

6: 1d4+1 tieflings on a stone temple ship, insular but not unfriendly

1d8+

7: A space trucker stopping off en route.

8: A space princess, running away from home. She might stay a while, work at the diner even. If you roll this when she’s already around, it means she’s got nothing to do and wants to hang out.

1d10+

9: 2d6 gnomes on a ramshackle ship, looks slightly too small to fit all of them. Boisterous, amiable.

10: 1d4 weird aliens that don’t seem to fully understand what’s going on but don’t cause trouble.

1d12+

11: An old friend of Gramps’, stopping by for a visit.

12: Delivery! You guys are a lot busier these days, huh?

2d12

13: An assortment of colourful characters from across the cosmos. Some you recognise, some new faces too. Another busy night at the diner. Gramps is proud.

14: 1d6 moon elves, considering moving back here.

15: Busy night! A family tips heavily. The person getting tipped offers to share some with you, since you practically rebuilt this place and all. 3d10 crazy space coins.

16: 2d4 moon elf hipsters. This place is cool now, apparently.

17: A travelling alien chef. Gramps might ask him to work here.

18: A grizzled bounty hunter. Has a suspicion his quarry may be close by.

19: A party of adventurers.

20: Impromptu dance party. Someone’s lined up some classics on the jukebox and everyone just seems to be in the right mood. One of those nights.

21: A tiefling businessperson who wants to buy the place from Gramps.

22: A company representative offering a lucrative deal if you (1d4) 1: sell their beer, 2: broadcast their gladiatorial sports channel, 3: expand into a casino, 4: expand into a strip club.

23: An unknowable and strange astral entity.

24: A supreme and benevolent celestial being.

1: It’s a quiet night tonight.

2: Two-tailed moon jackals barking at the crystal out back. Shoo, ya varmints! Go on, get!

3: A lone alien, stopping in for some grub while he refuels his ship. He doesn’t speak.

4: Delivery! Food for the kitchen, a replacement part for some gadget, something X ordered.

1d6+

5: Loudmouth no-good punk kids on a joyride.

6: 1d4+1 tieflings on a stone temple ship, insular but not unfriendly

1d8+

7: A space trucker stopping off en route.

8: A space princess, running away from home. She might stay a while, work at the diner even. If you roll this when she’s already around, it means she’s got nothing to do and wants to hang out.

1d10+

9: 2d6 gnomes on a ramshackle ship, looks slightly too small to fit all of them. Boisterous, amiable.

10: 1d4 weird aliens that don’t seem to fully understand what’s going on but don’t cause trouble.

1d12+

11: An old friend of Gramps’, stopping by for a visit.

12: Delivery! You guys are a lot busier these days, huh?

2d12

13: An assortment of colourful characters from across the cosmos. Some you recognise, some new faces too. Another busy night at the diner. Gramps is proud.

14: 1d6 moon elves, considering moving back here.

15: Busy night! A family tips heavily. The person getting tipped offers to share some with you, since you practically rebuilt this place and all. 3d10 crazy space coins.

16: 2d4 moon elf hipsters. This place is cool now, apparently.

17: A travelling alien chef. Gramps might ask him to work here.

18: A grizzled bounty hunter. Has a suspicion his quarry may be close by.

19: A party of adventurers.

20: Impromptu dance party. Someone’s lined up some classics on the jukebox and everyone just seems to be in the right mood. One of those nights.

21: A tiefling businessperson who wants to buy the place from Gramps.

22: A company representative offering a lucrative deal if you (1d4) 1: sell their beer, 2: broadcast their gladiatorial sports channel, 3: expand into a casino, 4: expand into a strip club.

23: An unknowable and strange astral entity.

24: A supreme and benevolent celestial being.

The Vending Machine

There’s a battered old device outside the front of the diner

that looks like some kind of space-age treasure chest. A slot in the side only

takes moon coins, the purple-metal currency of the lost moon elf empire. Gramps

might have one or two lying around, but if you want more you’ll have to find

them in the dungeon.

To receive an item, the correct price must be inserted into

the slot and the item’s code entered, as displayed on the front of the box.

Code

|

Cost in Moon Coins

|

Item

|

010

|

2

|

TranquiliTea: A type of carbonated

beverage, in a sealed can. Works as a health potion.

|

011

|

2

|

TranquiliTea Gomberry: A

popular variant of the classic canned beverage. Same thing, different

flavour.

|

012

|

3

|

Sweat Taste (Sports Edition): A

different brand of drink. Lurid, almost glowing blue. Restores one 1st

level spell slot when consumed. The drinker must then save against the rush

of energy or instantly cast a random 1st level spell.

|

013

|

2

|

Soul Chocolate: If

anything evil smells this on your breath they can’t steal your soul.

|

014

|

1

|

Dr Meeble’s One-Pot Meal: Dry

food in a little pot, adding water makes a kind of stew. A day’s rations,

barely.

|

015

|

3

|

Funkthistle: Pipeweed. You

can tell the smoke to do things for you.

|

016

|

4

|

Fisherman’s Ear: A mushroom

that causes mild hallucinations, numbs pain and allows the user to speak to

ghosts.

|

Whenever an item is purchased from the machine, roll 1d100

on the table below.

01

|

The item jams in the mechanism and doesn’t come out. It’ll pop out

next time you buy the same item.

|

02-99

|

The item comes out. Nothing special happens.

|

100

|

An extra random item falls out by mistake!

|

***

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)