I was considering not posting this, I felt it was a little rant-y. But I stand by the general premise, so here we go, see what you make of it. (Also the game I mention at the end has since been streamlined to the point that those travel mechanics are fairly different than how I wrote about them here lol.)

***

A few times during my GMing... career? Ew. Life? Oh dear...

A few times, I've tried to write specific mechanics, for whichever fantasy adventure RPG system I happened to be running at the time, to deal with overland travel. These, I surmised, would make travel a key component of the game, something to plan for and experience tension through, just like combat.

Crucially, they would make travel interesting, and fun.

Most gaming blogs or video channels or whatnots have a post somewhere about solving, or at the very least easing overland travel in D&D. Some of these thoughts are good, but most devolve into creating a subsystem, or wrangling existing mechanics into doing travel "better".

Here's the thing - within the context of these games, that's impossible. I was wrong, and so is anyone who writes travel rules for such an RPG.

***

One of the OSR blog posts I keep going back to is from Rogues and Reavers, and it defines the concept of a campaign frame. You can and should read the post here.

The thing I'm concerned with for now is the definition given for a frame:

A. Clear choices for the players to engage in, while still allowing maximum flexibility.

B. A model for the DM which guides them through the process of building this aspect of their campaign.

C. Rules for interacting with the frame in a meaningful way, from arbitration on the DM end to procedures on the player end

That, to me, seems like all the ingredients needed (outside of the mechanics themselves) for a great rule book. As for those mechanics - the only mechanics that are needed in the book are those that facilitate the campaign frame.

That's why I got rid of combat rules in my game about thieves. That's why D&D has rules for dying because a dragon breathed at you, or how likely you are to pick a lock on a treasure chest. Dungeons, and, indeed, dragons, are the campaign frame of D&D. You don't need anything else outside of the frame.

***

So, what does this have to do with terrible travel rules?

D&D - and by that I mean WotC, pre-WotC and every OSR game ever - doesn't include codified mechanics for overland travel beyond "here's how far you can go in a day, hexes are a thing".

This is not because good travel mechanics are impossible. It's because travel mechanics are not part of the assumed campaign frame of D&D.

"What? What do you mean, travel doesn't fit into D&D? It fits in perfectly! In my campaign, we do travel all the time! And besides, my group loves my travel rules! I added resource management for rations and terrain-based encumbrance tracking and..."

Hush.

Travel fits into D&D in the same way social interaction does. You can spend all session doing nothing else, but there have never been mechanics for it other than maybe a Charisma roll. Those mechanics are not needed. Your game may well be travel-heavy, but what the rules are about is not what the game is about - as we well know.

Oh, and your group doesn't love your travel rules. Even if they do, they like other parts of the game better. The actual D&D parts. D&D is about the dungeons and the dragons.

This is why the most obvious, and most correct, advice GMs are given when asking "how do I make travel more interesting" is to add an adventure site (dungeon) en route, or an encounter (dragon).

Overland travel is neither a dungeon, nor is it a dragon. Those are codified within the mechanics of the game, they are the campaign frame. Travel is just a thing that happens in between.

***

Do all travel mechanics in RPGs suck, then? No, of course not.

I'm working on a game - I write a lot of games, and even if they don't go anywhere I learn something from the design process. Anyway, it's a game with travel mechanics.

These mechanics are good. They make travel interesting. They offer, if you'll refer back to our definition of a campaign frame, A, B and C. I hope I can get the other bits sorted out, I'd like to let people play this some time.

The reason the travel mechanics work in this game is because it is a travel game. It's a game about journeys, going back and forth and all around between places on a map, life on the road. They are also, importantly, the only mechanics in the game - because they support the frame. Other mechanics are not needed.

D&D is not about those things - at least not in the way that people who write articles on how to do travel wish it was. When Gygax wanted to run overland travel, he played a whole different game.

Stop trying to make travel in your fantasy adventure game interesting. Unless it's a dungeon or a dragon, I don't want to hear about it.

PS: If you have a sci fi game and nobody cares about the starship mechanics - same reason. Your game probably just isn't really about the ships.

Tuesday, 26 June 2018

Thursday, 21 June 2018

Announcements: A Playtest! A Guild!

tl;dr: play my game here, help me make it here.

***

GRAVEROBBERS

***

GRAVEROBBERS

is a gothic fantasy heistcrawl RPG, with a feather-light ruleset inspired by the OSR.

Things I've written about it on this blog can be found here.

The Current State of the Game

Some folks have been expressing an interest, so I figured I might as well put the rules up, such as they are. You can get what I'm calling the Player Starter Sheet right here in a lil google doc.

The Player Starter Sheet has everything a player needs to know to make a character and play the game. As a GM, all you need to do is:

a) prepare a situation (a heist)

b) decide when to call for rolls (bearing in mind how the rules work)

b) decide when to call for rolls (bearing in mind how the rules work)

I feel like anyone who's GM'd an OSR game before can do this competently enough.

The Future of the Game

I'd like to eventually release a finalised ruleset, in a document along with GM advice, at least one starter adventure, various example hacks for the game, and a few of the most pertinent posts from this blog, rewritten to be relevant to Graverobbers specifically.

Any updates to the rules, additional content, and previews on a final product will be shared through the Graverobber's Guild.

|

| art by Nicoletta Migaldi |

The Graverobber's Guild

I'm setting up a Patreon, intended to:

- Support the making of Graverobbers and other games I'm working on

- Direct access to all updates on those games, and a direct channel to me for your feedback

- Serve as a kind of tip jar for folks who like this blog

- Direct access to all updates on those games, and a direct channel to me for your feedback

- Serve as a kind of tip jar for folks who like this blog

- Develop a community, so you can talk to each other and me about ideas

- Provide me with a direct line to the folks who most want to support me, so I can give you stuff

- Provide me with a direct line to the folks who most want to support me, so I can give you stuff

The Guild can be found right here. The only pledge level is $1USD per month.

This is not a payment for a service - it is an optional way for you to help me if you are able to and want to. I hope you will consider sending a little bit of spare change my way if you like what I do :)

PS: If you don't want to commit to a dollar a month, you can give a one-off donation by spending an amount of your choice on any of the products on my Gumroad online store.

This is not a payment for a service - it is an optional way for you to help me if you are able to and want to. I hope you will consider sending a little bit of spare change my way if you like what I do :)

PS: If you don't want to commit to a dollar a month, you can give a one-off donation by spending an amount of your choice on any of the products on my Gumroad online store.

Wednesday, 13 June 2018

Bastard Magic

I've written before about how I like practical magic in RPGs. Magical effects that feel real, occult, that affect things within the game world rather than the mechanics. Spells made of words, not bonus numbers and damage dice. Magic that feels like magic.

With that in mind, here is a new magic system of 30 spells that I'm calling Bastard Magic.

I wrote it as a magic option for my own game, but it's completely system neutral and fits into any fantasy RPG.

Each of the 30 spells comes with a full description that works as a guide for the GM, the player and the characters within the game. Each spell also comes with suggestions on how to begin thinking about using magic creatively.

You can download it for free right here.

With that in mind, here is a new magic system of 30 spells that I'm calling Bastard Magic.

|

| art by Eleanor Bergmann |

Each of the 30 spells comes with a full description that works as a guide for the GM, the player and the characters within the game. Each spell also comes with suggestions on how to begin thinking about using magic creatively.

You can download it for free right here.

Friday, 8 June 2018

The Postbox in the Woods (An Adventure)

Every child in the

village knew the legends of Taro-Taro. Half human and half spirit, a boy born

of a peach pit that hatched on a mountaintop, he was a hero who bridged our

world and the spirit world. When there was trouble with mischievous ghosts, or

the forest gods grew angry, Taro-Taro performed feats of cunning and strength

to restore harmony.

There was a shrine to

Taro-Taro, long ago, in what is now the Old Town Forest. Priests tended the

holy ground, and there was a sacred wooden box containing the wishes of

children, scrawled on paper leaves. For Taro-Taro had sworn an oath to answer

any honest request by the pure of heart.

However, the oath of a spirit is binding, and Taro-Taro soon began to grow weary. Every child is pure of heart, and their prayers came in great number at each festival and blessed day. While many were impossible requests or fell outside the hero’s purview, he still found himself forced by his own word to deal with every spiritual problem the locals had, no matter how inconsequential.

Before long, Taro-Taro

had had enough. In a tantrum, he grew a forest around the postbox overnight, enveloping

the old town and forcing the villagers to leave. They settled the

new town by the forest’s edge, cursing Taro-Taro. The once lauded hero, now

left in peace, rested within the trunk of an old tree, paying the monkey

god twelve gold coins to guard him as he slept.

The Adventure

The players are travellers from a nearby town, which is suffering

under a spirit’s curse. They hear the old legend and travel to Old Town Forest

to try and find Taro-Taro’s mailbox, and get the legendary spirit-boy to help

them.

If a message is written down and posted inside the box, Taro-Taro appears, bleary eyed. He begrudgingly agrees to do what he is asked, on the condition that the players smash the postbox to pieces.

If a message is written down and posted inside the box, Taro-Taro appears, bleary eyed. He begrudgingly agrees to do what he is asked, on the condition that the players smash the postbox to pieces.

Rumours

1: Taro-Taro is

dead.

2: Hide your swords from the wooden priests! They hate the glint of coin, too. Offends them.

3: If you find the old monkey statue, give it a gold offering. The spirits might leave you be.

4: Oh, you’re going into the forest? Sweet… Could you get me some of those mushrooms?

5: Some have gone wandering those woods, never to return. Maybe the monkey god cursed ‘em.

6: The forest is magic… It feels. Don’t hurt it. In fact, don’t hurt anything in there. It’ll get angry.

2: Hide your swords from the wooden priests! They hate the glint of coin, too. Offends them.

3: If you find the old monkey statue, give it a gold offering. The spirits might leave you be.

4: Oh, you’re going into the forest? Sweet… Could you get me some of those mushrooms?

5: Some have gone wandering those woods, never to return. Maybe the monkey god cursed ‘em.

6: The forest is magic… It feels. Don’t hurt it. In fact, don’t hurt anything in there. It’ll get angry.

The Map

Cut out the crossword from a free newspaper. This is your

map of Old Town Forest.

White squares are natural paths, littered with occasional

undergrowth and rubble. Black squares are “walls” formed of the crumbled

buildings of the old town, overgrown with dense foliage.

The central square is where the old shrine is, and within it

the mailbox.

Encounters

Roll 1d4 on the table below each time the players enter a

crossword square with a number in it.

Whenever an encounter ends in violence or wanton destruction

of the forest, increase the die rolled for the next encounter (1d4, 1d6, 1d8,

1d10).

1: Butterflies.

2: 1d4 deer.

3: A wild boar, angry.

4: Wooden priests. Make hollow knocking noises. Love quiet, hate metal.

5: A cursed monkey-man. Tells lies to get someone close enough to bite. The bitten grow tails.

6: A monkey who has found a cloak of invisibility. Harmless but annoying.

7: 1d4 savage, sharp-toothed apes.

8: Animated sap monsters, dripping from the trees.

9: Monkey mages. Mischievous. Can cast spells to cause deafness, blindness or muteness.

10: An animus of the forest, shambling piles of dirt and plant matter. Angry.

2: 1d4 deer.

3: A wild boar, angry.

4: Wooden priests. Make hollow knocking noises. Love quiet, hate metal.

5: A cursed monkey-man. Tells lies to get someone close enough to bite. The bitten grow tails.

6: A monkey who has found a cloak of invisibility. Harmless but annoying.

7: 1d4 savage, sharp-toothed apes.

8: Animated sap monsters, dripping from the trees.

9: Monkey mages. Mischievous. Can cast spells to cause deafness, blindness or muteness.

10: An animus of the forest, shambling piles of dirt and plant matter. Angry.

Features

Roll a die that encompasses as many of the numbers on the

crossword squares as possible (probably a d20). Cross out the number you roll,

and put a symbol in that square instead.

The symbol corresponds to one of the following features. Keep

rolling until you’ve added all four.

1: A small,

stagnant pond.

2: A stone totem of a fat monkey. Put a gold coin in its mouth and primates won’t bother you here.

3: Mushrooms grow here that cause a happy, light-headed haze when eaten. Monkeys love them.

4: A termite mound, the remains of its last victim cleaned to the bone. Best to find another route.

2: A stone totem of a fat monkey. Put a gold coin in its mouth and primates won’t bother you here.

3: Mushrooms grow here that cause a happy, light-headed haze when eaten. Monkeys love them.

4: A termite mound, the remains of its last victim cleaned to the bone. Best to find another route.

Remnants

If the players search the ruined and overgrown buildings of

the old town, they find:

1: Insects living

in the dark corners.

2: 1d4 copper coins.

3: A doll. There is an old man in the village who will recognise it from his youth.

4: A beehive.

5: Mushrooms growing from a dank patch of filth.

6: A child’s letter, intended for the postbox at the shrine. It asks Taro-Taro for a baby brother.

7: An old lucky charm, whittled into the shape of a monkey.

8: A gold coin.

2: 1d4 copper coins.

3: A doll. There is an old man in the village who will recognise it from his youth.

4: A beehive.

5: Mushrooms growing from a dank patch of filth.

6: A child’s letter, intended for the postbox at the shrine. It asks Taro-Taro for a baby brother.

7: An old lucky charm, whittled into the shape of a monkey.

8: A gold coin.

Old Magic

If the bodies of a boar, deer and butterfly are offered upon

a desecrated shrine, a powerful demon will appear to offer magic in exchange

for gold. He can grant one person a spell that lets them exhale a cold and

mighty wind, and teach the secret commands that all mountain birds heed.

The players learn of this ritual later in their adventures, and recall

the broken shrine to Taro-Taro, deep in the forest they visited all those weeks

ago.

Friday, 1 June 2018

The Graverobber's Guide to Gardening

I like magic to be made of actual words, rather than a set of mechanics, numbers or bonuses to this or that.

One of the many reasons for this preference is that players can read a spell description both in and out of character. The magic exists within the fiction of the world, rather than as a little meta note on a character sheet ("1d6 damage, 60ft range", that kind of thing).

Same with magic items. There are a bunch of strange plants in my world, so here's a guide to those that might be useful for the players to know about.

Same with magic items. There are a bunch of strange plants in my world, so here's a guide to those that might be useful for the players to know about.

It's written as an in-universe artefact that players could buy in a shop, or find in a greenhouse. Also serves the added bonus of getting across worldbuilding info in a gameable context - the only way that worldbuilding ever really matters.

I'm always adding to it, so feel free to do the same.

***

THE GRAVEROBBER'S GUIDE TO GARDENING

by Pirro, amateur gardener and retired graverobber

ITEMS & TOOLS

pot golems

Little round chaps made of clay,

these are handy for adventurers to plant things in. They follow you around, and

protect whatever’s growing in them.

sunstone

Casts a tiny bit of light that seems

to work just like sunlight. Handy for growing in dungeons or catacombs.

tajirian staff

A sanctified butterfly net. Bugs

caught within it become loyal, insofar as a bug can hold allegiance, until it

is next used.

wise man’s glass

Sunlight, shone through this little

magnifying glass, turns to moonlight, and vice versa. Might be good for growing

certain faerie plants.

PLANTS & FUNGI

boatleaf

These huge plants grow from the silt

in still water. Their leaves float atop the surface and are huge and hardy

enough to carry a person’s weight.

brambleroot tree

Its thorny roots lie close to the

surface, animating to snare those who step over them unwillingly. Called the

“flamingo tree” because of how its white leaves turn red after it feeds.

crabshell mushrooms

The cap of this fungus is round, flat

and hard. Good for a makeshift shield.

follybrush

A riverside flower whose thick pollen

stains the skin like dye. Traditionally used in makeup and facepaint, these

days only really seen during the three Festivals of Masks.

fuillement

The pale elves of the northern woods

make traditional clothing from the leaves of this plant.

gant’s root

This fiery and bitter root, when

chewed, is said to allow the user to speak with spirits of the dead. Some

legends vary and state that it simply keeps vengeful dead at bay, its strong

flavour stopping them from sucking one’s soul out through the mouth. Either

way, popular at Spirits’ March.

laddervine

Grows a foot a day, straight up a wall or surface.

Climbing it is as easy as walking up stairs.

lockseed

A plant whose flower contains a key

matching the lock its seed was planted in. The little plant normally takes a

week to flower.

meatweed

The leaves are thick with a fleshy

substance that fills them like gel fills aloe. Can be dried and made into

jerky.

paddlescum

Rank in taste but nutritious, it

grows like mould on stagnant water. The principle diet of trollspawn before

they grow legs and emerge from their birthing ponds.

shaking vine

These dry and brittle weeds susurrate

at the presence of certain magics, such as things turned invisible.

shufflers

Carnivorous plants that wander around

on their roots, searching out small creatures to digest in their acidic,

mouth-like flowers. Grow them, with caution, for their roots as a potion

ingredient.

sweetheart plums

Woodland elves brew a wine from these

fruits that functions a little like a love potion.

lumions

The unplanted bulb emits a glow, too

faint to notice in daylight but such that it can be seen in pitch black

darkness. (I am attempting to grow a variant that casts light like a candle

flame.)

wall anemone

A strange and fibrous plant that

grows in canyons. What appears to be its flower is in fact a fleshy, poisonous

appendage.

wayflower

Called tournescalier by the elves,

its plucked flower swivels around when held, always pointing to the nearest

staircase. The flower dies and withers one hour after being picked.

PESTS &

MONSTERS

bug ghosts

I don’t believe in them, but the old

gnome who runs the supply shop in Last Chance sprinkles his vegetable patch

with holy water every new moon, and his cabbages are flawless.

corpse bees

A grim but necessary part of

gardening in dungeons. They brew crimson honey in ribcage hives. Supposedly if

you can stomach it, it has healing properties.

pixie moths

The powder scales from their wings can

cause everything from itchiness to drowsiness to hallucinations. Lead them away

with the glint of gold instead of a flame.

tantalian slugs

They secrete a goo that increases the

sensations of pain and touch. Supposedly a party piece at elven orgies. Keep

the greedy beggars out of your plants with a little salt on the soil.

MYTHS &

LEGENDS

almaidalance

Most legends don’t specify the myriad

flowers that bloom wherever Alda, Lady of Spring, walks upon the ground. The

few legends that do mention one that has never been found in reality; a white

hibiscus whose petals are fine as glass. Could it really be a fiction?

divine pomme

An apple with skin like alabaster and

flesh like pure gold. The dish that the great hero Kyros served to the ocean

spirit Selene in the old legend that inspired the modern Sellenic Games, held

biannually in Meriscella. In the modern trial, champions must bring the finest

dish they can to a great feast at the end of the Games’ second week. (Once

someone tried to claim they had actually found the apple, I think? It was an

illusion or something.)

faerie

Not so much a legend any more as we

know it’s real, but the world of the fey contains innumerable plants still not

discovered! If I were still in the graverobbing business I’d happily lose

myself in that place… though I suppose that’s the trick.

sweetbeard

An old dryad, the only male one and said

to be the kindly king of all their kind. The sap from his luxuriant beard

bolstered heroes’ strength in old tales. One of the principle servants of

Cairen, Prince of Autumn, just like Selene is for Alda.

the world tree

Supposedly far beyond the eastern

steppes, an enormous tree holds up the sky. Travelling rabbitfolk tell of roots

like hills, and branches so big that entire forests grow on them.

Tuesday, 22 May 2018

Does An OSR Game Need Dedicated Combat Rules?

I'll segue into today's topic with an update on the status of the game I'm working on. It's kind of what prompted the question in the title - that and some recent conversation on the social platforms.

I was also working on a separate ruleset beforehand, for a heist game. There were various iterations, and I was largely happy with it, but it was more of a pet project than the Fantasy Heartbreaker. Then I started running a new campaign, and... well, I don't remember my thinking exactly, but the fantasy game has been absorbed into that heist game.

I mean, a dungeon crawl is just a heist anyway, we all know this. This is simply a ruleset that leans into certain aspects of the dungeon crawl over others, with a particular implied setting, all of which add up to make a more "heist"-themed game that still plays in the OSR style. I'm very proud of it so far, and I expect you'll be hearing more about it soon enough.

***

The heist game as it existed before the fantasy stuff got absorbed into it had no specific combat rules. Combat was a governed by a roll, like other things, and that was fine. It worked for the genre and tone of that system.

I had notions of bringing over mechanics from the fantasy ruleset to keep things in line with what I thought of as OSR - things like initiative, attack rolls, AC.

The core mechanic of the heist game is very different from d20+mod, and I had a lot of fun trying to adapt those classic concepts in new ways, thinking up new mechanics that delivered the same effects. But as I refined the game, playtested, drafted and redrafted, all those mechanics fell by the wayside.

In the latest iteration, the one I'm using to run stuff, combat is just a roll again. There are as many combat rules as there are rules for stealth, lockpicking or scaling a clock tower in the dead of night with a grappling hook. That is to say: describe what you want to do, and then the GM tells you to make a roll.

My designer brain, reared on 5e and now enamoured of the many DIY takes on traditional combat systems, keeps throwing up ideas on adding tactics, damage types, weapon categories. But nothing works as well for this system as the single roll.

***

My next thought, then, was "is this still OSR?". I know from Troika! that the old-school mechanics OSR games draw inspiration from don't have to be from D&D, and I know from Maze Rats that you can change the core mechanic until it's not recognisably D&D at all and still be considered OSR.

But no combat rules? Surely this was blasphemy? Was I turning my face from the DIY community entirely, and embracing some new, dark wilderness of game design, alone?

I mean... no. I don't think so.

***

One of the most persistent myths about the old-school style is that it's a numbers-first, tactical combat based, hack-and-slash style of gameplay. It's not. The game is lethal, and if you wish to avoid the many varieties of grisly demise on offer, you need to think creatively, avoiding and subverting combat scenarios rather than engaging in them.

But you knew that, you're smart. We all on the same page? Good.

So, then, quoth the as-yet-unaware, why do OSR systems have so many combat rules? As opposed to, say, rules for feeling things, or exploration? If the game is about things other than combat, why isn't that reflected in its ruleset?

Again, we know the answer: because the way OSR play engages with the rules is fundamentally different from most other schools of RPG design. Your character sheet is a list of the few limitations imposed on you, not a list of your awesome powers and skill trees. In something like Pathfinder, say, the character sheet represents all the cool stuff you can do. In an OSR system, the cool stuff you can do is everything else. OSR play is what's not written - what's written is there to ground the situation and make things difficult.

***

So, then, the if the purpose of the combat rules in an OSR system is to enforce lethality, the question we started off with remains. Does an OSR game need dedicated combat rules?

No. I don't think so.

What it needs is lethality rules - rules that ensure that when things go wrong, there are drastic and often fatal consequences. Rules that encourage the OSR playstyle - player ingenuity and calculated risk-taking - by providing a box the player is forced to think outside of.

The reason, then, that these lethality rules have been presented as combat rules since the days of yore is, obviously, partly because the hobby evolved out of wargaming. But if that was the only reason, they would have been replaced over the decades as RPGs moved further and further from their wargaming roots.

The main reasons, I think, are a combination of genre conventions and player agency. We expect the knight to have a sword, and know how to use it, while the wizard shoots fireballs from her trusty staff. Those are the special skills the characters offer, and since we can't roleplay physical danger at the table like we can social situations or intellectual puzzles, we need to have at least some idea of whether or not they will work in a given instance.

This ties heavily in to player agency. When your back's against the wall and combat's the only option, you want to know exactly what it is you can do - even if it is likely a fatal endeavour.

Combat rules do three things, then: enforce lethality, support the expected tone and setting of the system, and allow players options to fall back on when "standard play" (what I call just, like, talking), fails them. These are all Good Things. Combat rules are good.

***

So why was I having such a hard time grafting them on to my own system? Why did every attempt feel so inelegant? It is an OSR game, I still believe that. The playstyle is exactly the same. I eventually realised I'd just achieved that playstyle in a different way.

My game has its own rules to enforce lethality that aren't tied to damage. I'll likely detail them another time, or they'll be available to read once some form of playtest doc or rulebook comes out. But basically, rolls are inherently dangerous. Every one is a gamble with your character's fate, in one way or another, and with each failure you risk slipping closer and closer to death. The structure of lethality is very much enforced, even without standard HP mechanics or damage rolls.

As for supporting the expected tone and setting? Well, those are different in this game. It's not a gonzo Conan-esque dungeon crawl, it's kept too much of the heist flavour for that. I still run dungeon crawls in it, but the setup and tone are different enough that players don't expect their characters to necessarily be able to wield a sword, or use magic. In fact, character creation makes it very apparent how unlikely it is that either of those skills will be available. It's in a different genre, ish.

And finally, options to fall back on. The numbers on the sheet, the stuff outside of talking, planning, or using your surroundings or inventory in interesting ways. Those three things are the vast majority of any session, but what happens when those options fail? Combat mechanics sort that out by giving everyone some kind of mechanical sway on the deadly situation, however slight. Characters in my game still have mechanical abilities, but not everyone has an attack bonus. They'll be good in other ways - hiding from a monster, sneaking past it, running away.

Don't get me wrong - they can attack. Limiting player agency is maybe the biggest no-no for me in game design. They're just probably not going to be good at it. Making them good enough at a bunch of other stuff, and making that stuff more relevant, is an acceptable substitute, I've found.

***

So, to answer the question.

tl;dr: No.

I figured out that:

1. Lethality mechanics don't need to be distinctly combat-focused as long as failure can still lead to death and disaster.

2. Players won't miss dedicated combat rules if the setting and style make it clear that combat is unlikely to be relevant.

3. As long as the players have something to roll for when the shit hits the fan, they're happy, even if it's not a classic attack roll vs AC.

***

The only thing remaining, then, is compatibility with other OSR/DIY stuff, and I don't think the game's lacking anything by not basing itself on the standard model. The main point of conversion between systems is monster stat blocks, and since there aren't any combat rules, the game doesn't need 'em. You could absolutely run something like Tomb of the Serpent Kings in this system, no problem.

Well, that's me all rambled out. Exciting things to come, stay tuned.

I was also working on a separate ruleset beforehand, for a heist game. There were various iterations, and I was largely happy with it, but it was more of a pet project than the Fantasy Heartbreaker. Then I started running a new campaign, and... well, I don't remember my thinking exactly, but the fantasy game has been absorbed into that heist game.

I mean, a dungeon crawl is just a heist anyway, we all know this. This is simply a ruleset that leans into certain aspects of the dungeon crawl over others, with a particular implied setting, all of which add up to make a more "heist"-themed game that still plays in the OSR style. I'm very proud of it so far, and I expect you'll be hearing more about it soon enough.

***

The heist game as it existed before the fantasy stuff got absorbed into it had no specific combat rules. Combat was a governed by a roll, like other things, and that was fine. It worked for the genre and tone of that system.

I had notions of bringing over mechanics from the fantasy ruleset to keep things in line with what I thought of as OSR - things like initiative, attack rolls, AC.

The core mechanic of the heist game is very different from d20+mod, and I had a lot of fun trying to adapt those classic concepts in new ways, thinking up new mechanics that delivered the same effects. But as I refined the game, playtested, drafted and redrafted, all those mechanics fell by the wayside.

In the latest iteration, the one I'm using to run stuff, combat is just a roll again. There are as many combat rules as there are rules for stealth, lockpicking or scaling a clock tower in the dead of night with a grappling hook. That is to say: describe what you want to do, and then the GM tells you to make a roll.

My designer brain, reared on 5e and now enamoured of the many DIY takes on traditional combat systems, keeps throwing up ideas on adding tactics, damage types, weapon categories. But nothing works as well for this system as the single roll.

***

My next thought, then, was "is this still OSR?". I know from Troika! that the old-school mechanics OSR games draw inspiration from don't have to be from D&D, and I know from Maze Rats that you can change the core mechanic until it's not recognisably D&D at all and still be considered OSR.

But no combat rules? Surely this was blasphemy? Was I turning my face from the DIY community entirely, and embracing some new, dark wilderness of game design, alone?

I mean... no. I don't think so.

***

One of the most persistent myths about the old-school style is that it's a numbers-first, tactical combat based, hack-and-slash style of gameplay. It's not. The game is lethal, and if you wish to avoid the many varieties of grisly demise on offer, you need to think creatively, avoiding and subverting combat scenarios rather than engaging in them.

But you knew that, you're smart. We all on the same page? Good.

So, then, quoth the as-yet-unaware, why do OSR systems have so many combat rules? As opposed to, say, rules for feeling things, or exploration? If the game is about things other than combat, why isn't that reflected in its ruleset?

Again, we know the answer: because the way OSR play engages with the rules is fundamentally different from most other schools of RPG design. Your character sheet is a list of the few limitations imposed on you, not a list of your awesome powers and skill trees. In something like Pathfinder, say, the character sheet represents all the cool stuff you can do. In an OSR system, the cool stuff you can do is everything else. OSR play is what's not written - what's written is there to ground the situation and make things difficult.

***

So, then, the if the purpose of the combat rules in an OSR system is to enforce lethality, the question we started off with remains. Does an OSR game need dedicated combat rules?

No. I don't think so.

What it needs is lethality rules - rules that ensure that when things go wrong, there are drastic and often fatal consequences. Rules that encourage the OSR playstyle - player ingenuity and calculated risk-taking - by providing a box the player is forced to think outside of.

The reason, then, that these lethality rules have been presented as combat rules since the days of yore is, obviously, partly because the hobby evolved out of wargaming. But if that was the only reason, they would have been replaced over the decades as RPGs moved further and further from their wargaming roots.

The main reasons, I think, are a combination of genre conventions and player agency. We expect the knight to have a sword, and know how to use it, while the wizard shoots fireballs from her trusty staff. Those are the special skills the characters offer, and since we can't roleplay physical danger at the table like we can social situations or intellectual puzzles, we need to have at least some idea of whether or not they will work in a given instance.

This ties heavily in to player agency. When your back's against the wall and combat's the only option, you want to know exactly what it is you can do - even if it is likely a fatal endeavour.

Combat rules do three things, then: enforce lethality, support the expected tone and setting of the system, and allow players options to fall back on when "standard play" (what I call just, like, talking), fails them. These are all Good Things. Combat rules are good.

***

So why was I having such a hard time grafting them on to my own system? Why did every attempt feel so inelegant? It is an OSR game, I still believe that. The playstyle is exactly the same. I eventually realised I'd just achieved that playstyle in a different way.

My game has its own rules to enforce lethality that aren't tied to damage. I'll likely detail them another time, or they'll be available to read once some form of playtest doc or rulebook comes out. But basically, rolls are inherently dangerous. Every one is a gamble with your character's fate, in one way or another, and with each failure you risk slipping closer and closer to death. The structure of lethality is very much enforced, even without standard HP mechanics or damage rolls.

As for supporting the expected tone and setting? Well, those are different in this game. It's not a gonzo Conan-esque dungeon crawl, it's kept too much of the heist flavour for that. I still run dungeon crawls in it, but the setup and tone are different enough that players don't expect their characters to necessarily be able to wield a sword, or use magic. In fact, character creation makes it very apparent how unlikely it is that either of those skills will be available. It's in a different genre, ish.

And finally, options to fall back on. The numbers on the sheet, the stuff outside of talking, planning, or using your surroundings or inventory in interesting ways. Those three things are the vast majority of any session, but what happens when those options fail? Combat mechanics sort that out by giving everyone some kind of mechanical sway on the deadly situation, however slight. Characters in my game still have mechanical abilities, but not everyone has an attack bonus. They'll be good in other ways - hiding from a monster, sneaking past it, running away.

Don't get me wrong - they can attack. Limiting player agency is maybe the biggest no-no for me in game design. They're just probably not going to be good at it. Making them good enough at a bunch of other stuff, and making that stuff more relevant, is an acceptable substitute, I've found.

***

So, to answer the question.

tl;dr: No.

I figured out that:

1. Lethality mechanics don't need to be distinctly combat-focused as long as failure can still lead to death and disaster.

2. Players won't miss dedicated combat rules if the setting and style make it clear that combat is unlikely to be relevant.

3. As long as the players have something to roll for when the shit hits the fan, they're happy, even if it's not a classic attack roll vs AC.

***

The only thing remaining, then, is compatibility with other OSR/DIY stuff, and I don't think the game's lacking anything by not basing itself on the standard model. The main point of conversion between systems is monster stat blocks, and since there aren't any combat rules, the game doesn't need 'em. You could absolutely run something like Tomb of the Serpent Kings in this system, no problem.

Well, that's me all rambled out. Exciting things to come, stay tuned.

Wednesday, 16 May 2018

On Mermaids, Hashtag Mermay

So a bunch of artists on Twitter (and, I presume, your social media platform of choice) are doing a thing. It's been a thing for a few years now I think? Anyway, in the month of May, they draw mermaids.

I found all the art in this post from artists I follow and by searching the hashtag. Check em out and hire em for stuff.

Mermaids are also great for fantasy games. Here's the how and why.

Soundtrack for this post.

There are two types of mermaid; not in historical mythology, just in current fantasy art and media, as observed by me.

The first type is the classic, storybook - even, Disney - mermaid. Top half pretty naked lady or, less commonly, man, and bottom half big ol' fish. (Side note: as far as we can tell, mermen predate mermaids. Huh.)

The second type incorporates the fishiness throughout. Blue scale-like skin, fin-ears, kelp hair, even barracuda teeth or, god forbid, gills.

Before we get into things, it would be remiss of me to not mention the fantastic Kiel Chenier's upcoming Weird on the Waves pirate setting kit, in which mermaids are a playable race. He's teased the variants: top half fish, or left half fish, or one where the fish bits are all inside. Can't wait for that.

(I guess I'll tag him here so people can find his stuff? I still have zero idea how or why Google Plus is a thing, but I think this'll do it? +KielChenier )

Let's talk about the first one first.

These mermaids are perfect for your fantasy game. If you describe a skeleton floating blobbily in a square mass, that one player who's read the monster manual or been playing for 30 years is gonna go "Oh! It's a gelatinous cube!", to dumbfounded expressions from the rest of your group.

If you describe a naked woman coming out of the water, her lower half hidden beneath the waves, everyone's gonna be thinking the same thing. And when you describe her long, elegant tail flipping lazily in and out of the water, everyone's gonna be on the same page. Everyone knows what mermaids are. They share a prized place with dragons and unicorns as being seeped into the cultural consciousness of not just modern western civilisation, but pretty much the whole dang planet.

But while dragons are for killing, or avoiding, or maybe talking to but then at some point killing, and unicorns are for... I dunno, riding? Unicorns are boring. Anyway, these "type one" mermaids send out a pretty clear signal, unlike almost every other fantasy monster, that you can just talk to them. For us running our OSR games, this is a godsend. Yeah, it's a monster on a random encounter, but this monster is... nice. She's smiling, she's happy to help. Anyone's first port of call is going to be at least attempting communication.

And from there, mermaids can open up your world in other ways. Half of her's up here, sure, but half of here is very much from... down there. What you get is instant worldbuilding, the implication that at the very least there's a coral castle or a sunken fortress or a clan of merrily singing fishladies on a rock somewhere nearby.

An interaction with a monster that everyone instantly understands, that encourages communication and that, even in passing, fleshes out your world? As far as OSR play goes, that's a fucking win.

And sure, maybe they drown sailors for fun, that bit's up to you.

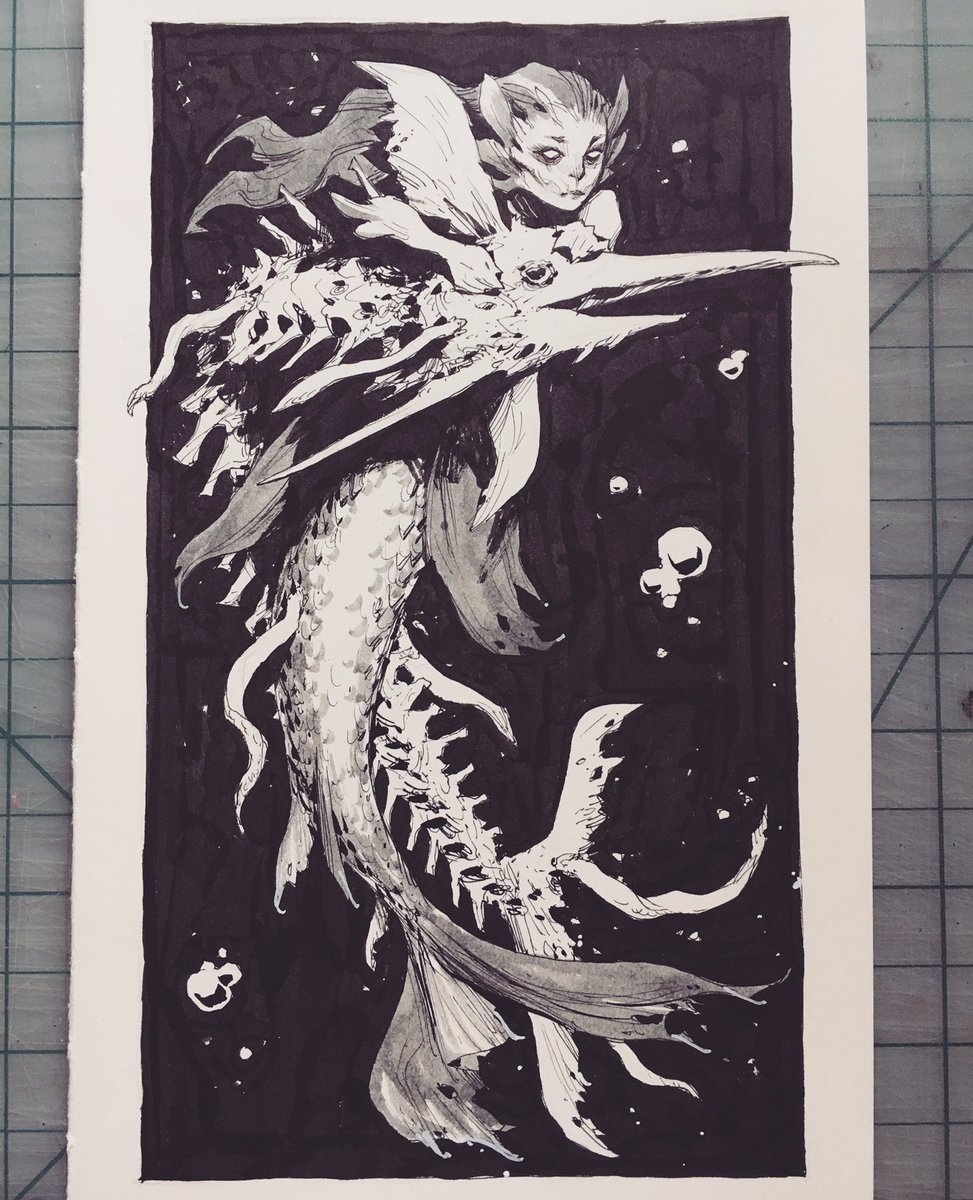

The "type two" mermaids then. The monsters.

Under the sea is weird. We know this. There are things down there that are more otherworldly than any sci fi movie's alien imaginings. These mermaids generally do a crappy-to-passable job of translating that otherness, but there's certainly untapped potential in the depths.

The problem here is, that if you want to go weird, there are better options than mermaids. The recognisable factor that makes the type-ones work so well puts you at a disadvantage here. It's like Cthulu: once a cosmic nightmare, vast and potent beyond our primate understanding, now a plushie you can get on a million Etsy stores, and the mascot for every other nerd-culture card game Kickstarter.

What these mermaids do best is in translating as animals, as beasts. I haven't played The Witcher III, but I've watched my girlfriend play it enough to know it's pretty great, and very Dungeons and Dragons. I once saw her rowing a little boat around the game's Viking-world analogue, when sirens attacked. I think that's what they're called in the game; in any case, sirens and mermaids have been conflated into mostly the same thing since forever.

These were no seashell bra-clad maidens, nor were they deep sea aliens. These were proper monsters. They were big, like sharks, and they tore into the boat as much as they did lovably gruff protagonist Geralt (I call him Jerry). We weren't knights on a quest, hearing the perilous siren's call, and we hadn't stumbled into anyone's non-euclidean eldritch domain. They were predators, and we were in their territory.

They weren't unknowable creatures from depths hitherto untravelled, or beautiful yet deadly temptresses. There are talking monsters in the Witcher, and fairytale stuff, but these just kinda... screamed. It was awesome. Sure they were vaguely human shaped, but the uncanny valley didn't even factor into it.

That's how you make type two mermaids work. Wait until the players are splashing around Amity Beach, and then let em loose. I'm not generally a fan of the whole "this monster is just an animal in its ecosystem, here's how it functions biologically" vibe, but as with my previous foray into trolls, sometimes it just works.

So there you go, some thoughts on mermaids. I think they're often overlooked, but worth your time.

They also feature in the setting of my current home game, and I'm trying to collate my notes into something playable so that I can share it. I'll likely slap on some art and a hexmap and call it a module. Stay tuned for news on when and how you can get it, probably in a couple of months.

There's a whole lot more than mermaids going on in my little setting, and you could certainly run a campaign without bumping into one. All I'll say is that I've managed to work both the "type one" and "type two" mermaids in there, and it's working very nicely.

It's pretty simple actually. Freshwater and saltwater.

I found all the art in this post from artists I follow and by searching the hashtag. Check em out and hire em for stuff.

Mermaids are also great for fantasy games. Here's the how and why.

Soundtrack for this post.

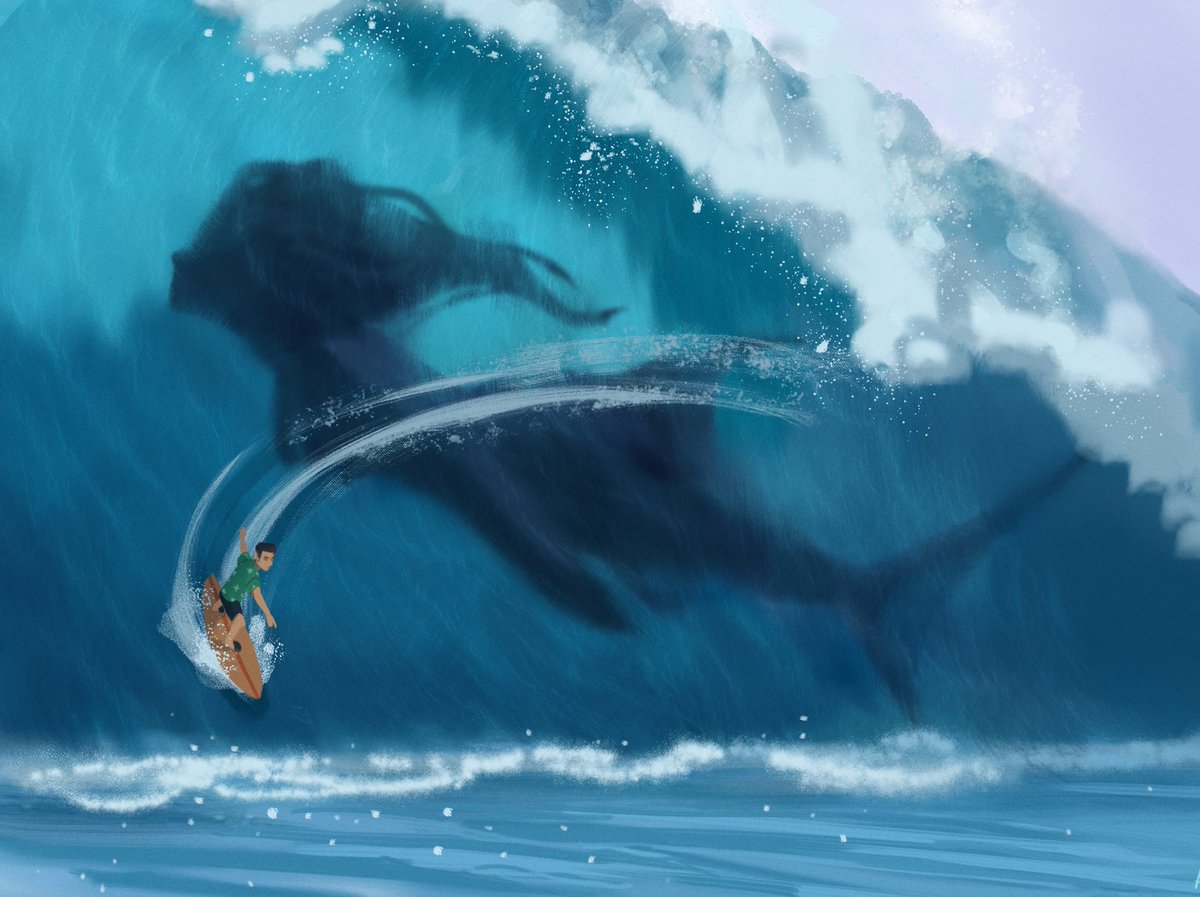

|

| art by @pkyrachu |

The first type is the classic, storybook - even, Disney - mermaid. Top half pretty naked lady or, less commonly, man, and bottom half big ol' fish. (Side note: as far as we can tell, mermen predate mermaids. Huh.)

The second type incorporates the fishiness throughout. Blue scale-like skin, fin-ears, kelp hair, even barracuda teeth or, god forbid, gills.

Before we get into things, it would be remiss of me to not mention the fantastic Kiel Chenier's upcoming Weird on the Waves pirate setting kit, in which mermaids are a playable race. He's teased the variants: top half fish, or left half fish, or one where the fish bits are all inside. Can't wait for that.

(I guess I'll tag him here so people can find his stuff? I still have zero idea how or why Google Plus is a thing, but I think this'll do it? +KielChenier )

Let's talk about the first one first.

|

| art by @anamericanghost |

These mermaids are perfect for your fantasy game. If you describe a skeleton floating blobbily in a square mass, that one player who's read the monster manual or been playing for 30 years is gonna go "Oh! It's a gelatinous cube!", to dumbfounded expressions from the rest of your group.

If you describe a naked woman coming out of the water, her lower half hidden beneath the waves, everyone's gonna be thinking the same thing. And when you describe her long, elegant tail flipping lazily in and out of the water, everyone's gonna be on the same page. Everyone knows what mermaids are. They share a prized place with dragons and unicorns as being seeped into the cultural consciousness of not just modern western civilisation, but pretty much the whole dang planet.

But while dragons are for killing, or avoiding, or maybe talking to but then at some point killing, and unicorns are for... I dunno, riding? Unicorns are boring. Anyway, these "type one" mermaids send out a pretty clear signal, unlike almost every other fantasy monster, that you can just talk to them. For us running our OSR games, this is a godsend. Yeah, it's a monster on a random encounter, but this monster is... nice. She's smiling, she's happy to help. Anyone's first port of call is going to be at least attempting communication.

And from there, mermaids can open up your world in other ways. Half of her's up here, sure, but half of here is very much from... down there. What you get is instant worldbuilding, the implication that at the very least there's a coral castle or a sunken fortress or a clan of merrily singing fishladies on a rock somewhere nearby.

An interaction with a monster that everyone instantly understands, that encourages communication and that, even in passing, fleshes out your world? As far as OSR play goes, that's a fucking win.

And sure, maybe they drown sailors for fun, that bit's up to you.

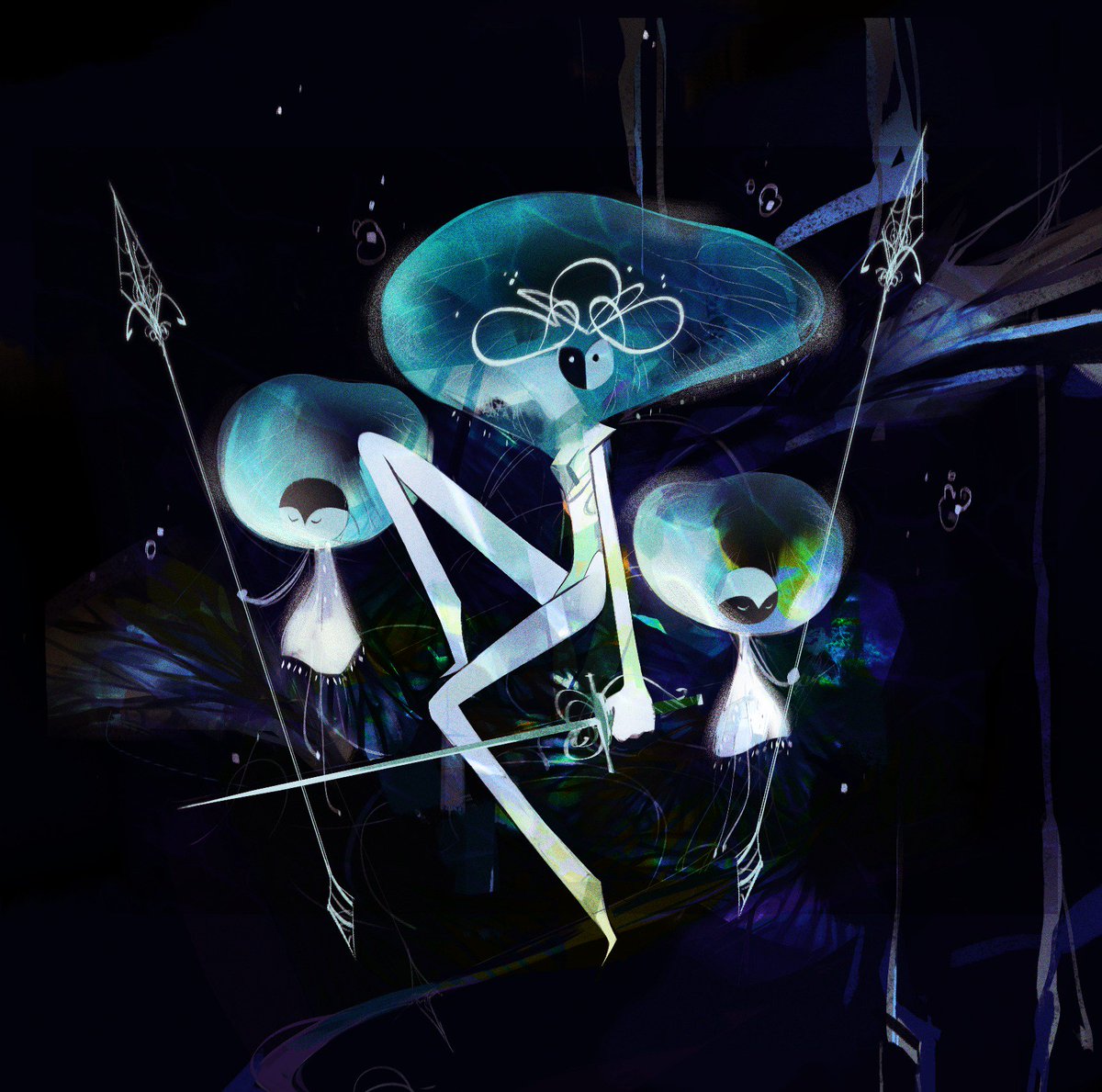

|

| art by @andrewkmar |

Under the sea is weird. We know this. There are things down there that are more otherworldly than any sci fi movie's alien imaginings. These mermaids generally do a crappy-to-passable job of translating that otherness, but there's certainly untapped potential in the depths.

The problem here is, that if you want to go weird, there are better options than mermaids. The recognisable factor that makes the type-ones work so well puts you at a disadvantage here. It's like Cthulu: once a cosmic nightmare, vast and potent beyond our primate understanding, now a plushie you can get on a million Etsy stores, and the mascot for every other nerd-culture card game Kickstarter.

What these mermaids do best is in translating as animals, as beasts. I haven't played The Witcher III, but I've watched my girlfriend play it enough to know it's pretty great, and very Dungeons and Dragons. I once saw her rowing a little boat around the game's Viking-world analogue, when sirens attacked. I think that's what they're called in the game; in any case, sirens and mermaids have been conflated into mostly the same thing since forever.

These were no seashell bra-clad maidens, nor were they deep sea aliens. These were proper monsters. They were big, like sharks, and they tore into the boat as much as they did lovably gruff protagonist Geralt (I call him Jerry). We weren't knights on a quest, hearing the perilous siren's call, and we hadn't stumbled into anyone's non-euclidean eldritch domain. They were predators, and we were in their territory.

They weren't unknowable creatures from depths hitherto untravelled, or beautiful yet deadly temptresses. There are talking monsters in the Witcher, and fairytale stuff, but these just kinda... screamed. It was awesome. Sure they were vaguely human shaped, but the uncanny valley didn't even factor into it.

That's how you make type two mermaids work. Wait until the players are splashing around Amity Beach, and then let em loose. I'm not generally a fan of the whole "this monster is just an animal in its ecosystem, here's how it functions biologically" vibe, but as with my previous foray into trolls, sometimes it just works.

|

| art by @hairytentacles |

They also feature in the setting of my current home game, and I'm trying to collate my notes into something playable so that I can share it. I'll likely slap on some art and a hexmap and call it a module. Stay tuned for news on when and how you can get it, probably in a couple of months.

There's a whole lot more than mermaids going on in my little setting, and you could certainly run a campaign without bumping into one. All I'll say is that I've managed to work both the "type one" and "type two" mermaids in there, and it's working very nicely.

It's pretty simple actually. Freshwater and saltwater.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)